What we do is what we blog:

04.03.2024 – New category added – Glossary

© Gerald Kozicz – Plan of the Gaurishankar Temple of Chamba Town, Chamba, India, 2024

Summary:

As on of our biggest updates to our blog so far, this week we are proud to present a new category: Glossary. It will, as the name suggests, act as a digital glossary for all the different terminology used in this blog and will feature imagery, descriptions, plans as well as a 3D model to make the contents of this blog as easy to understand as possible.

The new category can be accessed either via the site menu at the top of the page or directly HERE.

12.02.2024 – The Temple of Devi Kothi:

© Gerald Kozicz – Murals on the temple walls of the Śakti Devī Temple of Chatrarhi, Chamba, India, 2019

Summary:

In 2003, Eberhard Fischer, then director of the Rietberg Museum Zurich, together with Vishwa Chandra Ohri and Vijay Sharma, published a co-authored monograph on the Devī Temple of Devi Kothi as a special contribution to the ARTIBUS ASIAE series. This publication provides an excellent overview of not only the history of the temple and its art, but also introduces the history of the mountainous region at the Northwestern borders of Chamba.

Their description of the site gives an exact altitude of 2348 m above sea level (2003: 9). According to locals, the winters are harsh. Snow levels reach up to two meters and the village is cut off from the lower parts of Chamba for months every winter and spring.

The village itself has been built along a slope in a step-like pattern. The temple is among the buildings at the bottom of the settlement. Fischer, Ohri and Sharma reconstruct the long history of the site that is mostly inhabited by Brahmins. According to their findings, which include stone sculptures and architectural remains, the area must have been a centre of Brahmanic activities for more than a thousand years. Ruins of small stone temples and architectural fragments re-used in more recent vernacular buildings bear evidence of the existence of a former cluster of small temples.

The temple of Devi is of more recent date. An inscription first published by P.J. Vogel (1909: 35) mentions Raja Umed Singh as the builder and provides the exact date of 1754. The deity enshrined in the chamber is considered the sister of Cāmuṇḍā, the protective deity of Chamba Town. Once a year a procession takes the idol to Chamba for a symbolic reunion of the two sisters.

The architecture of the temple is a combination of masonry for the platform and the walls of the cella, and a wooden structure for the ambulatory and the pent roof structure. In addition to the idol sheltered inside, Raja Umed Singh commissioned murals for the embellishment of the exterior faces of the cella. The compositional order resonates the murals of the Śakti Devī Temple of Chatrarhi. There are however, two major differences. First, the paintings of the three walls completely lack the frames which separate the single scenes at Chatrarhi. This is to some extent related to the second difference. Unlike at Chatrarhi where frames dedicated to single deities mingle with frames showing episodes of the Devī Mahatmya, the first wall (according to the pradakṣiṇa order) and the second wall are exclusively showing scenes of Devī´’s war against the demons. As there is a single topic on each wall, internal separation of the scenes could be omitted. There is a fluid transition from one scene into the other.

The third wall – just as at Chatrarhi – is dedicated to the Life of Krishna. In contrast to the “Devī Mahatmya walls”, the artists used landscape elements and horizontal lines to create a visual narrative in three registers.

Regarding the style of the paintings, there is a significant difference to the Chatrarhi murals which hints at two different workshops. Also, the colours used differ. The paintings of Chartrarhi are much brighter whereas pastel colours dominate at Devi Kothi.

Finally, the wooden ceiling of the ambulatory must be mentioned, which is divided into 24 cassettes. Each cassette is visually subdivided into a swastika-square pattern with each of the arms dedicated to one figure. All cassettes are described in detail by Fischer, Ohri and Sharma (including) a plan and stitched image showing the whole ceiling (ibid: 39). Their publication also gives a lengthy and elaborate description and analysis of all the murals.

The publication by these three authors provides the so far most extensive discussion of a single monument of this part of the Hills or Brahmanic Western Himalayas.

Images:

References:

Fischer, E., Ohri, V.C. and Sharma V. (2003) The Temple of Devi-Kothi: Wall Paintings and Wooden Reliefs in a Himalayan Shrine of the Great Goddess in the Churah Region of the Chamba District, Himachal Pradesh, India. ARTIBUS ASIAE, Supplementum, Vol. 43.

Vogel, P.J. (1909) Catalogue of the Bhuri Singh Museum at Chamba, Chamba.

29.01.2024 – The Mural Paintings of Chatrarhi:

© Gerald Kozicz – Murals on the temple walls of the Śakti Devī Temple of Chatrarhi, Chamba, India, 2019

Summary:

According to O.C. Handa (2001: 164) the Śakti Devī Temple of Chatrarhi is held in higher esteem than the Lakṣaṇā Devī Temple of Bramaur/Brahmapura. Handa draws his conclusion from the fact that the goddess enshrined as a medal cast statue is referred to as Adi Śakti (the highest or ultimate śakti) and also from art historical analysis. The temple has indeed received remarkable attention by various scholars despite its location which – until the modern road was built – had been difficult to reach. The academic interest had been triggered by the exceptional wood carvings of the door frame and the ceilings of the cella and the circumambulatory as well as the wooden columns and brackets of that corridor. Notably, little attention has been paid to the mural paintings along the outer walls of the cella, which can be viewed while doing the pradakṣiṇa (walking along the circumambulatory path). The murals reflect the Western Himalayan painting tradition of the 17th – 18th century which was influenced by the artistic style of the Mughal Court painting tradition that was en vogue during that epoch. While the paintings are completely ignored by Goetz and even from Mira Seth’s “Wall Paintings of the Western Himalayas”, the most elaborate discussion of the subject in the regional context, Handa at least makes a short mention – simply noting that murals exist at Chatrarhi including the assumption that they had probably been commissioned by Raja Umed Singh (regn. 1748-1764). One published photograph (pl. 21, no identification provided in the caption) depicts the Samudra Mathana (“Churning the Ocean”) scene.

In the course of field trips, three temples with murals were documented. All three monuments are dedicated to a form of Śakti Devī or Durgā: Chatrarhi, the temple of Devi Koti and the temple of Shakti Dera. Obviously, the painting tradition was, after all, related to the Sakti cult.

At Chatrarhi, the paintings were structured in a grid pattern with frames providing the visual background. Accordingly, the paintings appear like a picture gallery. They are organised in two horizontal rows all around the cella. At the entrance wall (facing North), only two such frames flank the wooden portal on each side. According to the pradakṣiṇa tradition the visitor turns left and circumambulates the cella in a clockwise direction. The East wall is dedicated to episodes of Durgā fighting various demons as well as depictions of scenes such as the mentioned Samudra Mathana. For example, one frame shows Harihara, the composite form of Siva and Visnu with their respective mounts. There seems no clear narrative story line along this wall. It is however obvious that Devi and her various forms or emanations play a major role in the overall concept. This becomes even more evident at the Southern wall which is completely covered with scenes from the Devimahatmya, the fight and victory of Devi over the demonic forces. Devi is shown in different forms of combat, with one or several foes.

Two frames show her receiving homage and/or requests by the (male) gods. Unfortunately, the Southern wall shows severe damage, as it had probably been exposed to natural forces before the outer face of the corridor was mantled with wooden boards. At the Western wall – i.e., toward the end of the pradaksina, the programme centres on the Life of Krishna.

Images:

References:

Handa, O.C. (2001) Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples, New Delhi.

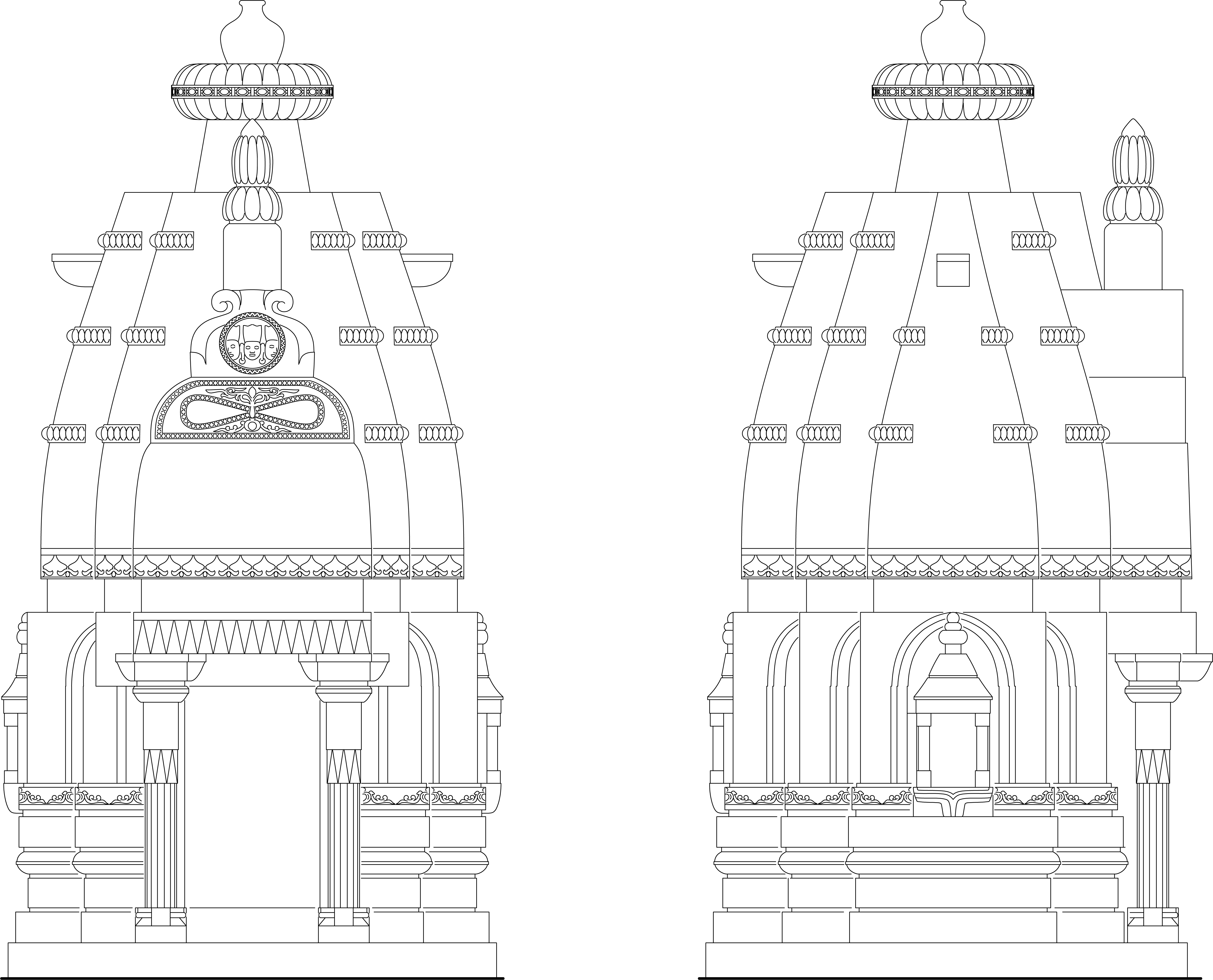

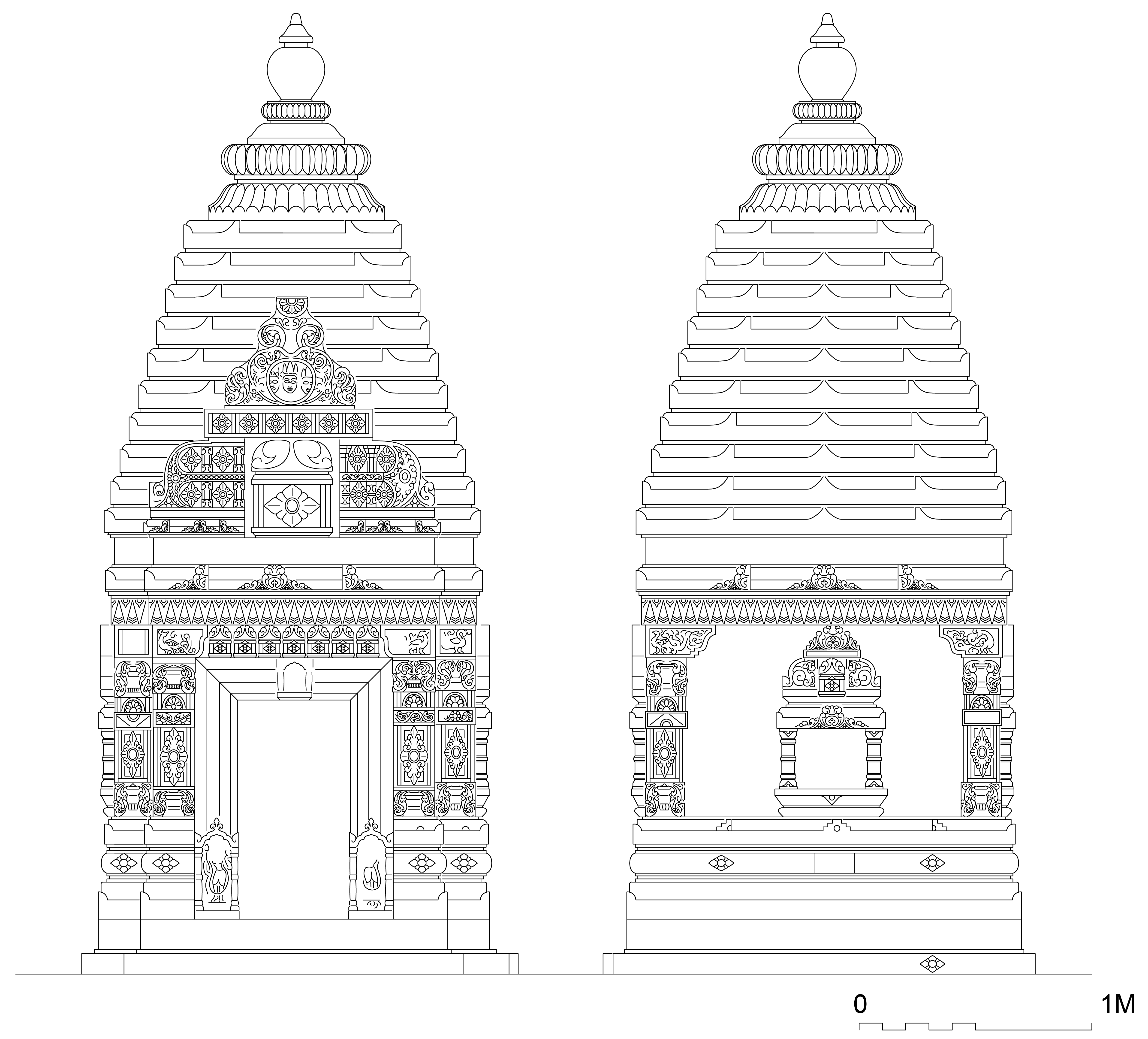

31.07.2023 – A Minor Temple of the Chaurasi Compound of Brahmapura:

© Gerald Kozicz – Minor temple (left) situated within the Chaurasi Compound, Brahmapura, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

The Chaurasi Compound of Brahmapura has received much attention by various scholars which resulted in a number of major publications starting with entries in J. Ph. Vogel’s “The Inscriptions of the Chamba State”. These discussions however, largely if not exclusively, focused on the three highlights of the site: the wooden components of the LakṣaṇadevῙ Temple, and the Narasiṃha and Manimahesh stone temples as well as the famous gilded sculpture of the bull Nandi in front of the later.

Besides these three major monuments, several smaller shrines are distributed over the compound area – buildings which appear to be of far lesser architectural quality, size and religious significance. Despite some visible signs of veneration and ritual activity, they are obviously treated with less respect and their maintenance appears poor. Likewise, these monuments have received little attention by scholars except a short general note by Cynzia Pieruccini (1997: 180).

This entry is dedicated to one of those minor shrines. The small monument is located to the East of Nandi, i.e., to the Northeast of the Manimahesh and the Southeast of the Narasiṃha Temples. On first sight, there is nothing spectacular in this structure – a simple Nagara stone temple with one bhādra projection (dvi-aṅgha floor plan), an almost plain śukanasa pediment above a simple porch created by a short roof resting on two fluted columns and a square chamber, and the usual āmalaka on top. Hardly any decoration can be identified along the surface. Some iconographic features are found on the door frame, but these areas are completely obscured by the two pillars of the porch, which are placed at short distance in front of the jambs. Nonetheless, this small temple deserves a closer inspection as it triggers a number of questions regarding the history of architecture in the region as well as the scientific approach towards the matter.

© Gerald Kozicz – Elevation of the West side of the Narasimha Temple of Brahmapura, Graz, Austria, 2023

First of all, the outer shape and silhouette. As mentioned above, the temple is dvi-aṅgha. All three sides except the entrance facade have a central bhādra niche. The corner pilasters completely lack the usual distinction between base with the pūrṇagata (pot with flower) image, the shaft and capital, again including the pot imagery. They seem completely blank. Only at the south-eastern corner there are traces of a former lozenge-diamond element visible, which are also found elsewhere (cf. Kharura Temple 3 of Chamba Town). All these three components of the pilaster have the same width, whereas elsewhere they are clearly separated visually by different widths. The lack of formal distinction between the components of the pilasters and loss of decoration causes the elements of the pilaster to meld into a single shape. This results in a niche-like design that frames the actual bhādra niche. The same effect occurs in the corners (karna).

Another particularity of the design that is already visible in the silhouette is the absence of a proper cornice that usually separates the jaṅghā walls from the upper parts of the temple. Instead, the capitals of the pilasters border the recess above the jaṅghā walls.

The shikara tower, with its curvilinear vertical bands, is an exact continuation of the dvi-aṅgha shape of the main body of the temple (mandovara with garbhagṛha inside) below. This appears like a natural design, but actually it is not. Temples of comparative size in Chamba Town – e.g., Temple 2 and 3 of Kharura and the Vishnu Temple of Chauntra – display different floor plan grids for their main bodies and their towers. Kharura Temple 3 has no proliferation at the ground floor at all. It is eka-aṅgha. Its śikhara tower however, is based on a tri-aṅgha plan with two proliferations. This is a result of the śukanasa pediment, which is found on each face of the śikhara. The same design principle can be noted at Chauntra where the floor plan of the temple is dvi-aṅgha and the śikhara tower displays a tri-aṅgha plan. It is worth noting that the proliferations of the two levels do not relate to each other. While the overall design appears coherent due to the aesthetic qualities of the decorative composition, the architectural form obviously was dealt with flexibility. The Brahmapura shrine has only the essential śukhanasa above the entrance. All the bhādra niches are without śukanasa above.

There are two more features that demand mention now. One feature is the continuation of the central vertical band of the śikhara with a strong proliferation up to the capstone of the tower (skanda). This results in a clear cruciform shape along the complete vertical which is unusual for the region. It recalls the architecture of the plains and other parts of northern India where the central band sometimes even vertically extends beyond the skanda.

The second feature is the high round stone shaft on which the āmalaka rests. It is not cylindric but slightly conical, i.e., its inclination conforms to the inclination of the śikhara and contributes to the overall aesthetic quality of the temple. The skanda as an upper border of the śikhara is almost absorbed into this continuation. It is however the height of the conus that explains a feature of Chamba architecture which has become a characteristic of temple architecture of Chamba: the octagonal roofs. Such roofs demand a certain height of the shaft because the super-structure of such roof must fit beneath the āmalaka. In Kulu the shafts are of lesser height and we don’t find comparable roofs around Naggar where there are numerous old Nagara temples, neither do we find such constructions along the Sutlej. In the Central Himalayas, e.g., at Jageshwar, a completely different super-structure was used for protective roof constructions. A sort of “table-like frame” was the choice of the builders there (cf. Chanchani 2019: 98, fig. 3.18). It is a comparatively unstable method and the choice for the frame might be explained by a comparatively short shaft which would not allow the system developed in Chamba. This remains however, a hypothesis which demands further inspection of temples in the Central Himalayas.

The amalaka of the Brahmapura shrine is crowned by a stone vase.

It becomes apparent from first glance at the front facade that the temple must be of more recent date than the two large Nagara Style monuments of Brahmapura, perhaps even more recent than the construction of the temples at Chauntra and Kharura in Chamba Town. The śukanasa completely lacks decorations except the sunken medallion with the tri-mukha image of Siva and a low-relief of a beaded band below. An interesting detail is the pinnacle above. It appears like a later addition. Even if so, the uppermost part should at least be mentioned. It looks like an elongate āmalaka, almost like a type of pumpkin with an attached hat. The element below comes comparatively close to the classical āmalaka, but is too elongated still. These two elements again rest on a cylindric shaft.

As for the other parts of the surface, the remains of a lozenge on the pilaster have already been mentioned. Besides that, a band of stylized textiles runs horizontally above the recess at the bottom of śikhara. The śikhara itself displays three corner amalakas along the corner bands. Otherwise, an unusual candraśālā (dormer window) motif on the uppermost layer of the vedibhanda is the only ornament that can be clearly identified.

Despite is simple architectural form and the poor state of preservation, this temple still adds to the wider picture of architectural history of Chamba. Perhaps it was its minor status and insignificant position within the compound which allowed the builders to introduce features which were not common in the region.

Images:

References:

Chanchani, N. (2019) Mountain Temple, Temple Mountains, Seattle.

Pieruccini, C. (1997) ‘The Temple of Lakṣaṇā Devī at Bharmaur’, East and West 47, nos. 1–4, 171–228.

17.07.2023 – The Ruined Kṛṣṇa Temple of the Nurpur Fort:

© Gerald Kozicz – Kṛṣṇa Temple of the Nurpur Fortification, Kangra, India, 2018

Summary:

While the majority of ruined monuments in the Kangra region display patterns of damage related to the devastating 1905 Earthquake, the present state of presentation of the Kṛṣṇa Temple on the plateau of the former Nurpur palace and fort most certainly derives from human activity. The remains display a clear cut right above the vedibhanda which hints at well-organized dismantlement of the temple. Whether it was already in a ruined state or not at that point is impossible to say.

The remains of the temple show a lay-out which is unusual for the region. It displays three spatial units along the main axis. Most unusual is the shape of the main chamber (garbhagrha) which was based on a combination of an octagonal and a star-shape. The remaining lower part of the door jambs to the sanctum and the carvings along the vedibhanda are still preserved. It is clear from the colours, that the builders used two different kinds of stone, one reddish (used for the sanctum) and one greyish-white (used for all other parts).

Images:

03.07.2023 – Another Syncretic Sūrya from the Lakṣmī-Damodara Temple?:

© Gerald Kozicz – Kṛṣṇa panel of the Lakṣmī-Damodara Temple of Chamba Town, Chamba, India, 2018

Summary:

The significance of Vaiṣṇavism in Chamba is also reflected by the presence of depictions of scenes or even complete stories of the life of Kṛṣṇa who is considered as one of the avatāras of Viṣṇu. Visual narratives can be also found in the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple Complex. According to O.C. Handa (2010: 27), such panels are “attributed to Balbhadrvarman (CE 1589-1641)”. Handa published a stone plate depicting scene of Kṛṣṇa’s childhood which he located at the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple, the main temple of the complex. This panel is today enshrined in the southern bhādra niche of the Lakṣmī-Damodara Temple. The visual narrative is structured by a system of lotus stems with the various deities placed on the flowers. Of particular interest is the vertical axis which not only has the main scene in the centre and Viṣṇu on top, but also two four-armed male gods who apparently hold two flowers in their central hands while the right upper arms seem to hold a club. While the flowers clearly hint at the sun god Sūrya, the club signal a syncretic form incorporating Vaiṣṇavite imagery. The syncretic forms which merge the potency of Sūrya with Śivaite power have already discussed in the Sūrya entry (9.1.2023). It might also be mentioned that one of these four-armed Sūryas is found inside the rear bhādra niche of the Lakṣmī-Damodara Temple. Although no major temple dedicated to Sūrya has been documented from Chamba Town area, the cult of the sun god is still omnipresent in town.

Images:

References:

Handa O.C. (2010) Ancient Monuments of Himachal Pradesh. Museum of Kangra Art, Dharamshala.

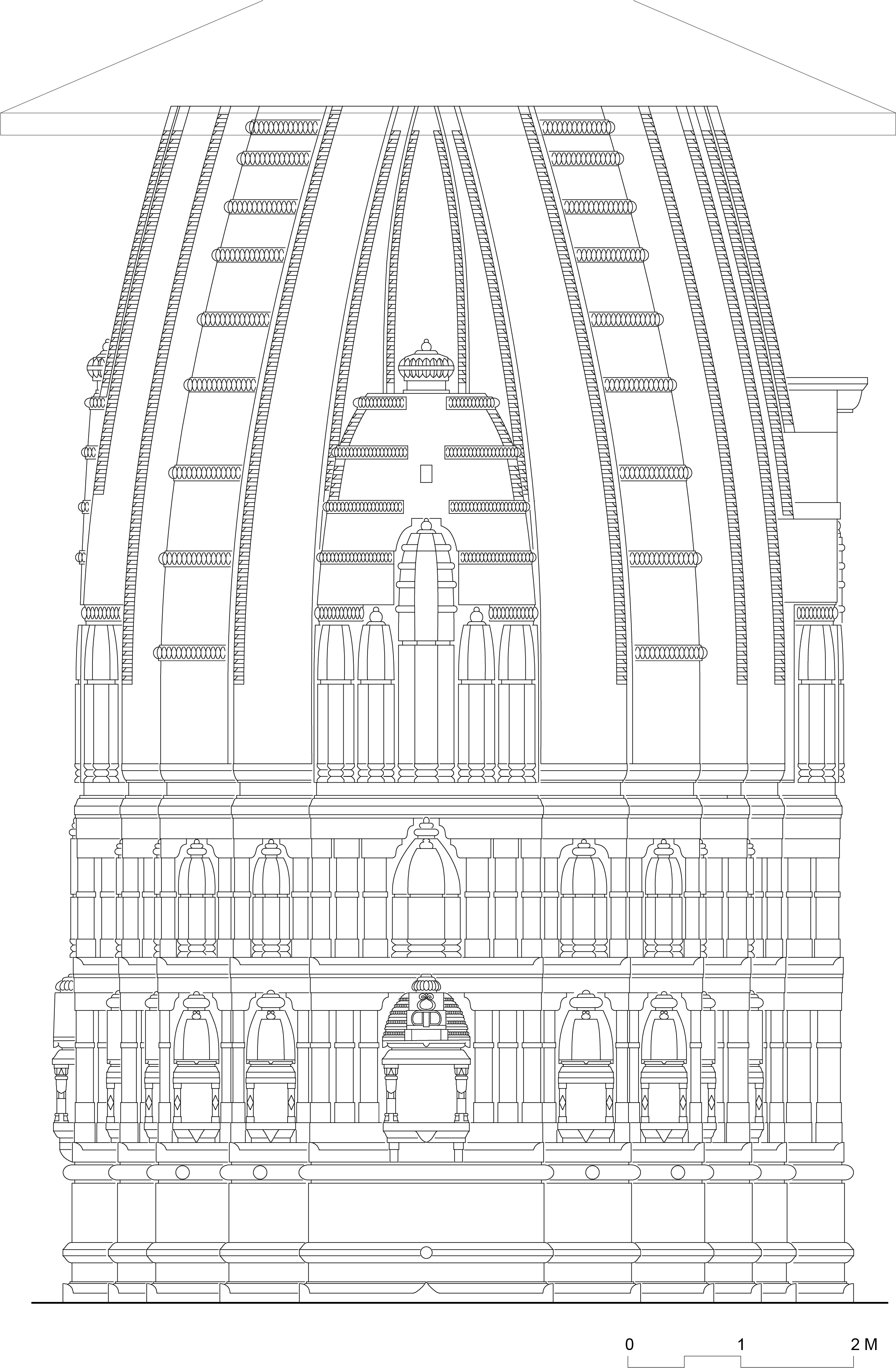

26.06.2023 – The Narasiṃha Temple of Brahmapura: The consequences of a misreading of textual sources

© Gerald Kozicz – Foundation of the Narasiṃha Temple of Brahmapura, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

The skyline of the temple compound of Caurasi at Brahmapura, the former capital of the first eponymous kingdom of the Chamba region is dominated by three elements: first, the Manimahesh temple on the central platform facing North; second, the huge ancient deodar tree to its west; and third, the Narasiṃha Temple at the northern end of the compound facing the Manimahesh Temple. These two nagara stone temples are regularly mentioned in publications about the architecture of the Hill States and are also mentioned in the Encyclopaedia of Indian Architecture edited by Michael Meister and M.A. Dhaky wherein they are discussed in Chapter 29 on the architecture of Himachal, an entry contributed by Krishna Deva (1991: 95). The mention is brief and dates the temples to the 10th century based on an inscription on a copper plate issued by King Yugakar Varman (r. ca. 940-960). The copperplate names – or rather seems to name – the Queen Tribhuvanrekha as the actual donor of the Narasiṃha. This evidence plus dating has never been critically reviewed and the two temples have been accepted as almost contemporaneous to the early temples of Chamba Town despite obvious differences on all levels. Instead, scholars seem to have deliberately ignored the differences and never looked into the actual architecture (e.g., Thakur 1996: 69-70, and Handa 2010: 46-47). Since the Manimahesh Temple is considered the older of the two, this central monument has been dated to around 940.

The major clue that calls for the review of the dating was already provided by J.Ph. Vogel who first translated the inscription of the copperplate and published his analysis in his Antiquities of the Chamba State, Part I (1911:101). He translates the inscription as it has later been cited and used for dating of the sites, but Vogel also adds a footnote which is crucial – and it is this footnote that has been overlooked by all the scholars in the following. The footnote says: The word Narasiṃhasya has evidently been added, it is not impossible that the grant was originally made to another deity. Vogel’s tentative explanation for the oddity is not convincing as he writes: But the name may have been simply modernized at the time when the character of the plate was no longer understood.

Also, on the previous page (Vogel 1911: 100) in the main text Vogel notes that the first opening stanza of the text is actually dedicated to Siva which he considers “remarkable” since Narasiṃha is the lion avartāra of Viṣṇu. Evidently, there is no proof that the copperplate refers to the Narasiṃha Temple as it is rather the opposite. And as we will see in the following, there is neither architectural evidence that would sustain such an early dating of the two temples.

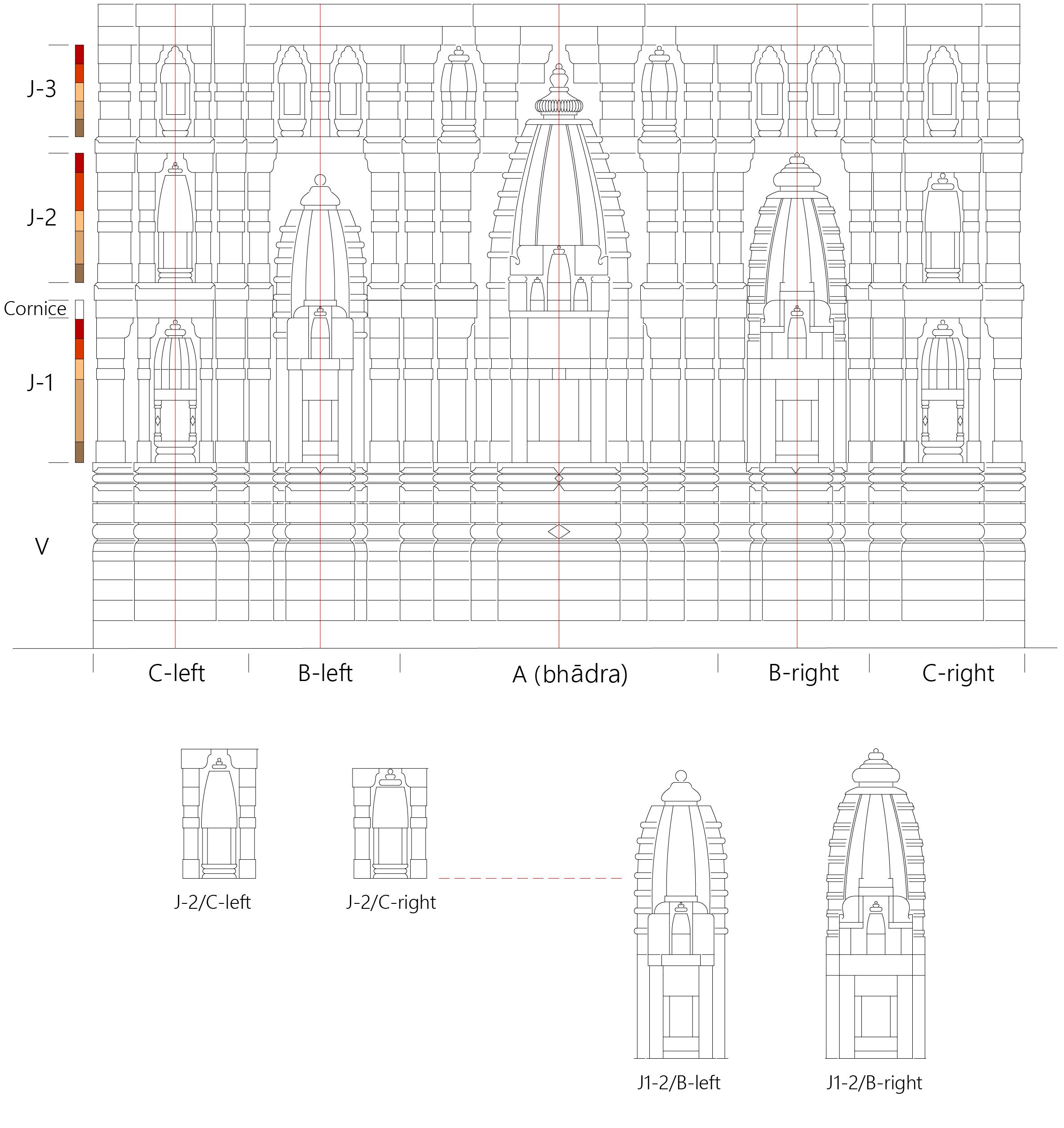

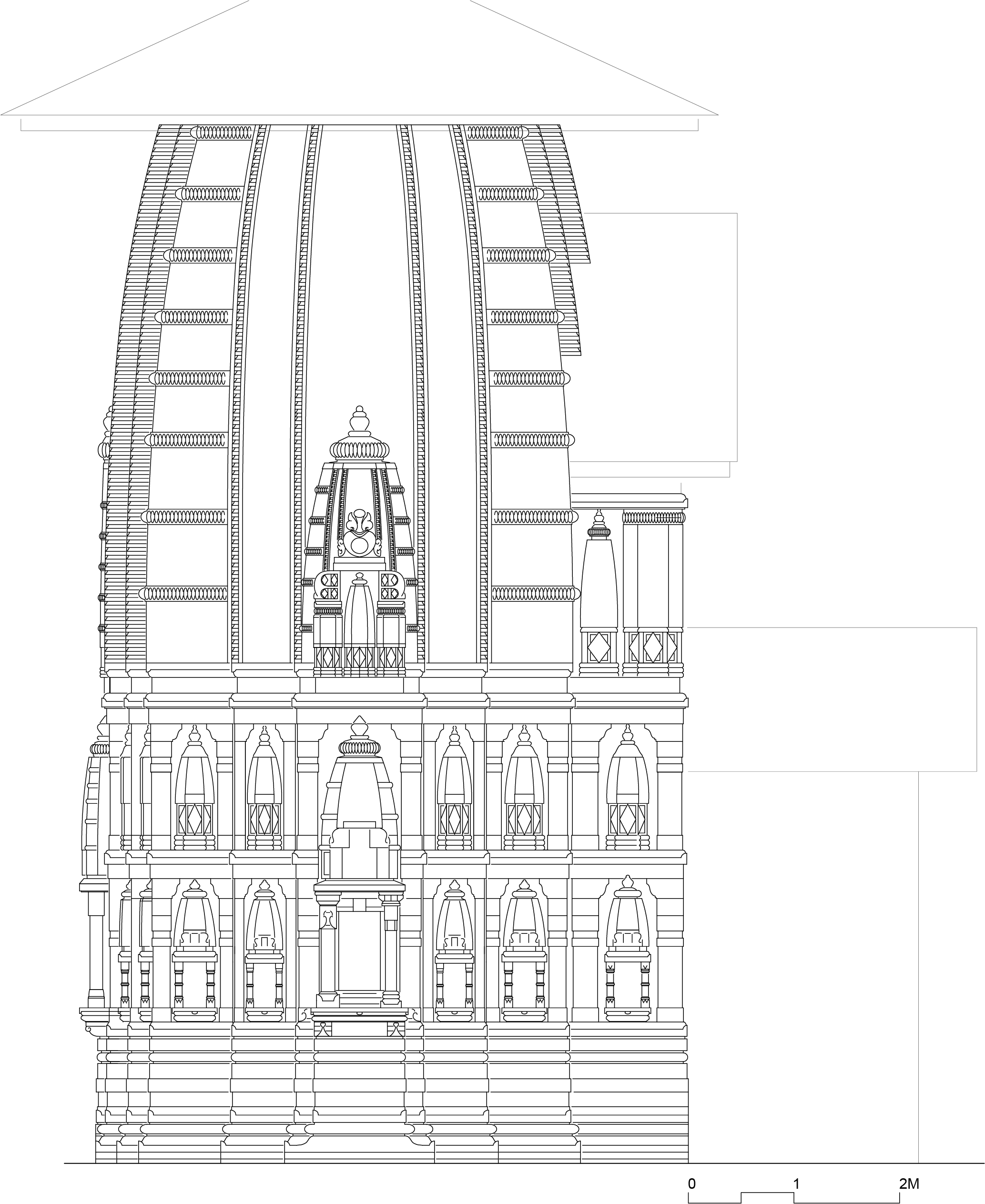

© Gerald Kozicz – Elevation of the West side of the Narasimha Temple of Brahmapura, Graz, Austria, 2023

Already the first impression when approaching the two nagara temples tell a trained eye that they are different to the large temples of Chamba Town (cf. the Damodara Temple) as they appear clumsy and bulky in shape. A direct comparison of the elevations based on ortho-photographs of the Narasiṃha Temple based on image-based 3D-models provide a clear picture of the situation. While the Chamba temples all have central bhādra niches (cardinal niches of the facades) which extend over two levels of the jaṅghā walls, the Narasiṃha has only “single-story” bhādra niches. Also, the extension of the bhādra-aedicule beyond the kanta above (the recess that separates the jaṅghā walls from the śikhara tower above) is not experienced at Brahmapura. Bhādra aedicule and the śikhara aedicule above seem rather separated. The aedicule on the śikhara which usually displays the classical pediment design (śukanasa) of nagara architecture lacks the round gavāksa motif in the center. The omission of this standardised component is unusual for a large temple.

Deviations from architectural principles continue with the designs of the jaṅghā wall flanking the bhādra proliferation. As can be seen clearly in the drawing (and the ortho-photograph), the width of the jaṅghā wall to the right is significantly wider than the one to the left. Even if we keep in mind that the Narasiṃha Temple has been damaged in the 1905 Kangra Earthquake, such deviation as we find it here cannot be explained by that disaster. First of all, there are no traces of cracks and shifts of masonry in this part of the building. Second, the difference of width between the aediculae ascertains that this asymmetry in the design was not caused by alterations to the original structure. Now, symmetry is one of the paramount principles of design and the accuracy with which it had been followed at all the other early temples is remarkable. It either hints at a major change of architectural principles or a decrease of building technology. Either way, such development could have hardly taken place within a decade. If we look at the decorative elements along the wall, the lozenge or diamond has been applied as an almost exclusive motif throughout the surface making. The result is a monotonous repetition that hardly adds to the artistic and aesthetic qualities to the monument. Such simplification of the visual language is typical for later temples.

Another obvious deviation from the architectural concept of the temples of Chamba Town is found in the roofing. At Chamba Town, the major temples have double-roofing of the śikhara tower and a pent-roof over the porch, while at Brahmapura only the śikhara tower is covered. This was not a random choice by the those who were in charge of the Brahmapura but a consequence of a major difference in the architectural concept. While at Chamba Town (and elsewhere, e.g., Kulu) the porch was made as a separate part that projected from the main body of the temple, the porch of the Narasimha was almost fully integrated into the main body. What remained at the outside was a minimal proliferation from the central cruciform shape of the central temple. As a consequence, the pediment above the entrance was reduced from a separate architectural component to a mere aedicule – and such aedicule did not demand a separate shelter. The antarāla (porch) thus became a mandapa (ante-chamber).

Now that we have reached the entrance area, we may continue with stylistic features that again clearly distinguish the Narasimha Temple from all early Chamba temples. The side walls of the mandapa have niches which display a style that recalls the niches of the Rajnagar temple and temples of Kharura which were apparently influenced by Mughal design. The door frame is – also because of the narrow mandapa – reduced to insignificance in regard to size as well as artistic quality. In this regard the design resembles the Kharura Temple 3.

As can be seen from previous entries in our blog, the door frame presents the religious context of the temple to the pilgrims and adherents, and it was the most prominent part of the iconographic programme. At the Narasiṃha Temple, is has almost vanished. Only the river deities are shown, but the quality is just poor and does not compare to any of the stone works from the 10th century. Such clumsy craftsmanship clearly hints at a date much later than what scholars have so far claimed for the construction of the temple. Architectural evidence clearly places the Brahmapura temples closer to the Rajnagar temple and the Kharura temples than to the temples of the 10th century.

To summarize this entry: The study of the architectural data call for a shift of the dating of the Narasiṃha Temple. It calls however, also for a serious methodological change in the studies of Himalayan art and architecture, a review of established methodologies which often place textual evidence over actual hard facts derived from the analysis of material culture. And it calls for re-introduction of what is fundamental for proper architectural discussion: accurate drawings, diagrams and sketches.

Images:

References:

Handa O.C. (2010) Ancient Monuments of Himachal Pradesh. Museum of Kangra Art, Dharamshala.

Thakur, L. (1996) The Architectural Heritage of Himachal Pradesh, New Delhi.

Vogel, J. Ph. (1911) Antiquities of Chamba State: Part I, Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series XXXVI, Calcutta.

05.06.2023 – Vaiṣṇavism as a State Religion: Images of Vaikuṇṭha through the Ages:

© Gerald Kozicz – Vaikuṇṭha in the niche of the Lakṣmī-Damodara temple, Chamba, India, 2018

Summary:

The significance of Vaiṣṇavism in the religious history of the Chamba region is well ascertained by sculptural evidence from Swai, where the influence of Kashmir manifested in art. In Kashmir, the three-headed form of Vaikuṇṭha was the most prominently venerated. In addition to the Vaiṣṇavite images already introduced in the entry of August 1st, 2022, there is a second stele of Vaikuṇṭha installed in the compound wall of Swai. It depicts Vaikuṇṭha in standing position. The lower pair of hands, which rested on the personified weapons (maze and disc) are lost. A third stele from the same site is now in the Bhuri Singh Museum (labelled “Vishnu Vaikunthamurti: Village Sawaim, Himgiri, Churah”, and dated to the 8th century). Vaikuṇṭha is depicted in seated position on his vāhana Garuda who holds a vase in his inner pair of hands and grasps two cobras with the outer pair. The thick curls of the hair-dos recall the visual idiom of post-Gupta styles. The boar and lion heads are in a higher position than the central head and are depicted as if they were emerging from the crown.

The popularity of Vaiṣṇavism continued with the foundation of the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple and the respective temple complex. Although Śivaism became increasingly popular, images of Vaikuṇṭha were continuously produced and installed. One stele is prominently placed inside the northern bhādra niche of the Lakṣmī-Damodara temple. The images follow the pattern of the Swai image in the Bhuri Singh Museum except for the inclusion of Lakṣmī. The goddess is leaning against Vaikuṇṭha‘s left thigh rather than sitting on him. The boar and lion heads are emerging from the side of the main head. Another feature of interest is the architectural design of the backrest which prominently features two pillar-like jambs topped by śikhara tower-like finals. The stele is datable to around 1000 CE.

A more recent image is installed inside the Viṣṇu shrine at Chauntra discussed in the previous blog entry. This shrine is still venerated by the local neighbourhood and the image is thus displayed in a ritual context – and it is partly covered by textiles. Garuda is depicted on the pedestal.

Images:

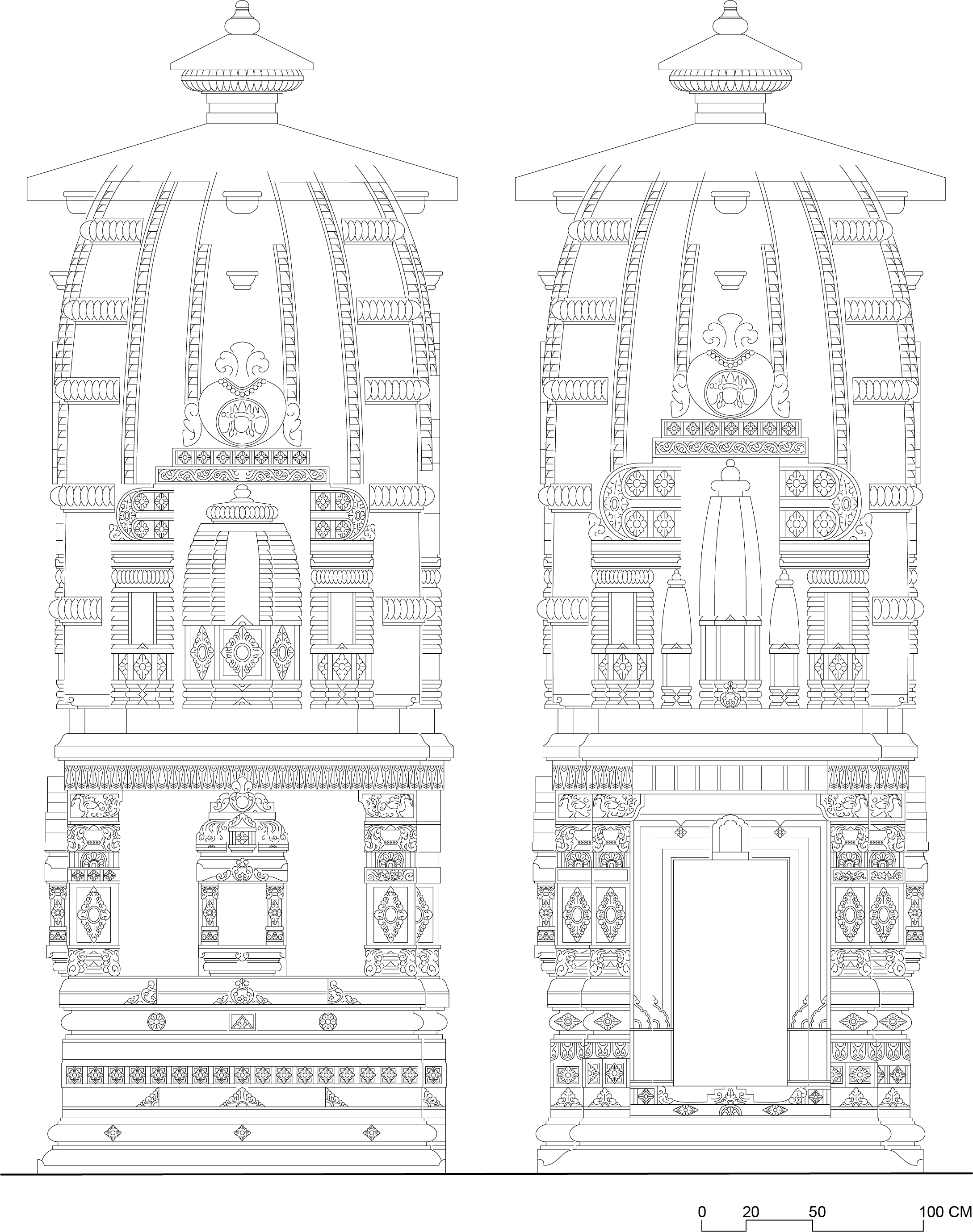

22.05.2023 – The Small Shrine of Viṣṇu at Chauntra, Chamba:

© Gerald Kozicz – Small Shrine of Viṣṇu at Chauntra, Chamba, India, 2018

Summary:

Chauntra is a residential area of Chamba Town to the East of the palace. There, four small temples are clustered around a small square. Two are placed next to each other on a platform. A photograph displaying their rear sides was chosen by Sethi and Chauhan as the cover image of their Temple Art of Chamba. Their discussion (Sethi and Chauhan 2009: 52-53) of the site however is limited and the architecture of these two temples is not discussed. One temple is nowadays placed inside a walled private garden and not open to the public. The fourth temple faces the two temples on the platform and is accessible from the street. This temple enshrines a four-armed stele of Viṣṇu Vaikuṇṭha. The shrine is of small size and cannot be accessed – only a crouching position allows the veneration of the idol. The ceiling is of the lantern type. One niche is in the centre of each of the lateral walls. Regarding the overall impression one may note a certain disproportionate arrangement which might hint at a later enshrinement of the stele.

In fact, the other imagery that has survived on the temple rather supports a Śiva affiliation although Śivaite imagery were also incorporated into the temples of other Brahmanic currents. But first of all, it is Gaṇeśa, the son of Śiva and Pārvatī who resides in the centre of the first lintel of the door frame. A small antarāla forms a spatial passage between the outside and the sanctum. On the pilasters of the lateral walls of that porch Gaṅgā and Yamunā, the River Goddesses, are in their appropriate position at the very bottom. Above them, two roundels mark the middle section of the respective pilaster. The roundel above Gaṅgā displays an eight-petalled lotus flower while the facing roundel above Yamunā displays a kneeling figure who is turned towards the sanctum. The figure depicted in the centre of the architrave above the porch is difficult to identify. It looks like a saint rather than a deity.

The central round field of the śukanasa above the porch which would have been indicative of the affiliation of the temple, is lost. Some of the stonework is still well-preserved but otherwise the temple also obviously also not well-maintained. This is clear from the plants which grow from its śikhara tower with their roots drilling through the masonry along the joints.

The shrine temple faces North. It has three bhādra niches and displays a dvi-aṅgha plan, i.e. a proliferation of the central field resulting in a cruciform floor plan. The niches which are empty today, and their framing pilasters are well carved showing the usual vessels, lotus and diamond motifs. The horizontal field above each niche displays three aediculae. Each niche has a decorated “threshold”. The decorative frame of the western niche differs from the others. It has two crouching lions on the pedestal and a Gaṇeśa on the lintel. these images clearly hint at Durgā as the original deity installed in this niche. Her prominent presence would again hint at a Śivaite shrine rather than a Vaisnṣṇavite sanctum – but this however remains speculative.

Images:

08.05.2023 – The Temples of the Kharura Area of Chamba 3: A Śikhara Tower Sheltering Bees:

© Gerald Kozicz – Śikhara Tower in the Kharura Area, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

Next to the temple with the “elephantine brackets” stands another nagara-type shrine. The temples are placed on two adjacent platforms, just separated by a step. This entry focuses on the temple on the lower level. It faces South, i.e. the street. Along the western side of the platform runs a narrow lane. The walls of the platform include fragments and components of a dismantled temple which have been re-used to embellish the two visible faces of the foundation. The temple is based on a simple square plan with three niches on the rear and lateral faces. Still it displays all the major decorative and symbolic elements that can be found on the large-size temples. Besides the number of proliferations and the related aediculae, the major difference to larger temples such as the Gauriśankara Temple of the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Compound is the contraction of the porch. The frontal pediment and its architectural features are still there, but the actual porch is omitted from the architectural and spatial concept. It must also be noted, that the structural and visual connection between the central aediculae (bhādra niche) and the corresponding part above, i.e. the aediculae on the śikhara of the large temple is well articulated, the recess (kantha) between śikhara and the aediculae below marks a clear border. While the two form a unit within the concept of the large temple, they do not display such visual unity in the case of the Kharura temple.

© Gerald Kozicz – Elevation of Temple 3 of the Kharura neighbourhood in Chamba, Graz, Austria, 2023

The first lintel above the entrance is adorned with an image of Gaṇeśa while a navagraha (Nine Planets) panel is placed above. The Three Faces (trimukha) of Śiva are shown inside the central roundel of the śukanasa and also on the other three sides of the śikhara. The corners of the śikhara are vertically structured by corner amālakas. The roof of the and the amālaka on top are protected by the usual two-layered canopy roof.

A gilded vase serves as the top-most final of the temple. The erection of the temple must therefore predate the issue of King Chhatar Singh’s order to embellish all temples of Chamba with gilded finals in response to Emporer Aurangzeb’s command to demolish the temples in 1678 CE.

Today, the temple not only serves as the shrine for a modern image of Krishna (Sethi and Chauhan 2009: 103) but also shelters Himalayan bees which occupy the cavity in the upper part of the śikhara. The entrance to their dominion is at the northern face of the temple.

Images:

References:

Sethi, S. M. and Chauhan H. (2009) Temple Art of Chamba, New Delhi.

03.04.2023 – The Temples of the Kharura Area of Chamba 2: The Temple with the Elephantine Brackets:

© Gerald Kozicz – Temple with “elephantine brackets”, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

Two temples are placed on platforms on opposite side of the road of the stepped temple introduced in the previous entry on the Kharura area of Chamba Town. Sethi and Chauhan (2009: 112-113) briefly mention “elephantine brackets” and the Hanuman on the śukanasa above the portal. The elephants face the outside and they are highlighted today with orange colour. The same colour is applied to two lion heads at the base of the lateral walls of the porch – again facing outside. When it comes to architecture, the perhaps most intriguing aspect of the frontal elevation is design of the inward arms of the brackets. They clearly form a Mughal-style entrance to the portico – a design not noted elsewhere so far in the town.

The temple is said to have suffered severe damage in the 1905 Earthquake like most of the temples in the area. A significant number of slabs are without decoration and bare witness of repair works and replacements of original members of its original architectural structure.

The elephantine brackets mentioned by Sethi and Chauhan are not without predecessors in the temple architecture of Chamba. Elephants are also depicted in comparable positions at the lower part of the śukanasa of several temples of the Lakṣmī Nārāyaṇa Complex. They are difficult to see because they are hidden behind the eaves of the respective pent roof that shelters each temple porch.

Images:

References:

Sethi, S. M. and Chauhan H. (2009) Temple Art of Chamba, New Delhi.

27.03.2023 – The Temples of the Kharura Area of Chamba 1: The Temple with the Stepped Roof:

© Gerald Kozicz – Temple with a “stepped roof”, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

Among the temples listed by Sethi and Chauhan in their Temple Art of Chamba, we find six temples in a neighbourhood called Kharura located to the East of the palace. The authors mention these temples belonging to Brahman families. Unfortunately, not a single image illustrates the brief description. Neither do the mentions contain a sitemap or a sketch that allows to ascertain the exact connection between the textual description with the various monuments in the area. One description which can still be clearly identified with a building on the ground refers to a structure with a “stepped roof”.

Sethi and Chauhan (2009: 102) highlight several interesting aspects of the shrine which – according to the authors – had suffered severe damage in the 1905 Kangra earthquake but also show significant traces of insufficient maintenance. These include the “niches like Rajput balconies with cusped arches”. Today, only the western niche can be viewed since the other perspectives are completely blocked by a neighbouring house to the South and stored building material on the eastern side. Sethi and Chauhan further note the design of the columns and capitals, which reflect the impact of the art of the Mughal court. They also draw attention to the kīrtimukha on the capital.

Gaṇeśa is depicted in the lalatabimba position above the entrance, i.e., the central field of the first lintel. As usual, the elephant-headed god is heavily coated with orange colour which hardly allows his identification. The figure appears to be four-armed. Above, the Nine Plates (navagrahas) are lined up. They too, can only be identified by the lotus symbols held by the far-left figure which signal Sūrya. Otherwise, they show severe traces of abrasion.

Images:

References:

Sethi, S. M. and Chauhan H. (2009) Temple Art of Chamba, New Delhi.

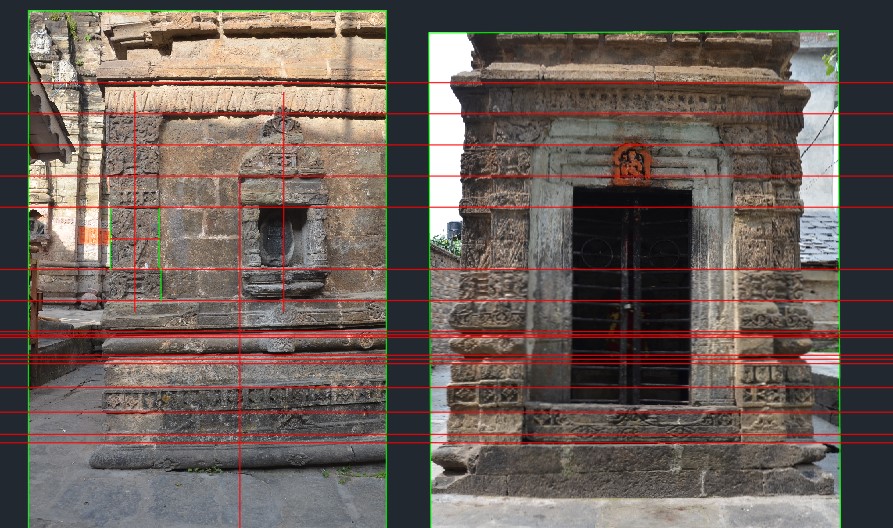

20.03.2023 – Workflow Update 3: How to plan for / in less than ideal situations:

© Gerald Kozicz – reconstruction process, overlay between lineart and photograph, Graz, 2022

Summary:

This week’s update to our workflow tab will show how we deal with situations, where our previously mentioned photogrammetry pipeline – either though incomplete photographic documentation or difficult situations in the field – fails or is just not applicable. It will show the remarkable results and the potential that can be achieved with the help of simple sketches and manual reconstruction.

The update can be accessed either via the site menu at the top of the page or directly HERE.

13.03.2023 – The 1905 Kangra Earthquake: A Disaster for Communities and Architectural Heritage:

© Gerald Kozicz – Kangra Fort, Kangra, India, 2016

Summary:

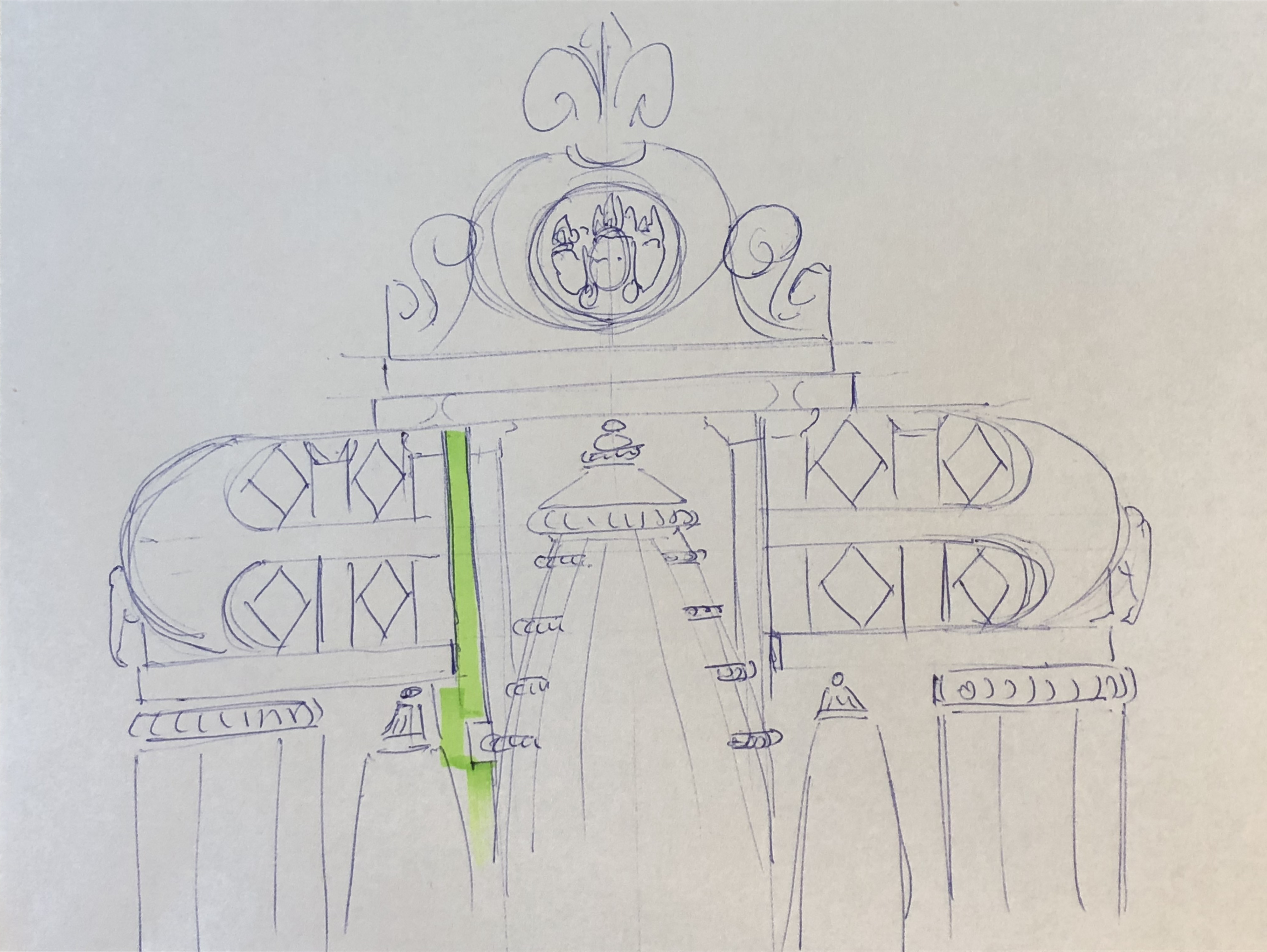

The regions along the Himalayan Range have always been exposed to natural threats due to tectonic factors, causing earthquakes and landslides in the aftermath. One of the worst disasters of the recent centuries was the so-called Kangra Earthquake on April 4th 1905. This earthquake also hit the region of Chamba right to the North of Kangra. We may assume that the damage already noted on the portal of the Chamesan Champāvatī Temple of Chamba was caused by that event. Quite similar patterns of damage can also be noted at the Gauriśankara Temple inside the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Complex. There the lintels of the outer face of the antarāla (porch) show the same kind of cracks. They run quite through the architraves that carry the load of the śukanasa above. A major vertical crack is also visible along the śukanasa between the central field and the left lateral part (see the images of the December 26th 2022 entry, and the sketch below). The śukanasa of the Lakṣmī -Damodara has a similar albeit narrower crack through the right lateral part of its śukanasa ‘s front – and the Chandra-Gupta Temple’s śukanasa displays abrasion which quite reminds on the Chamesan Champāvatī Temple.

Likewise, the main temple of the complex after which it had been named, the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple too, has a whole portion of its śikhara tower with fillings of comparatively new, non-original stone elements on its southern face. It is very likely that this repairs were carried out after 1905.

© Gerald Kozicz – Sketch drawing showing the crack along the śukanasa of the Gauriśankara Temple of the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa, Graz, Austria, 2023

As for Kangra, J.P. Vogel provided a summary of the devastating event in the Archaeological Survey Annual Report 1905-6 (finally published 1909). Therein he provides a number of comparisons of states of preservation of monuments before and after the earthquake (Plate 2). His first account is on the Kangra Fort and Town and includes a description of two major temples inside the fort, which had been the strongest fortification of the Western Himalayan Hill States in medieval times. Vogel refers to the two temples as the Śitalā and Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa but also notes, that there were no actual hints to confirm the dedication to any of the respective deities as there were neither idols or inscriptions. The temples were standing next to each other in a yard close to the top of the fortified area facing North. Regarding their architectural concept and layout, these temples completely differ from the Chamba temples and this entry will therefore focus on a brief comparison between the two systems by having a look at the remaining rear wall, i.e. the wall portion from ground level to the kaṇṭha (recess below śikhara) of the larger of the Kangra Temples, the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple.

On first sight, the Kangra temples look quite similar to the Chamba temples as the decorative patterns and motifs are widely identical – only at Kangra the patterns are even more elaborate. The ornaments were the dominant visual factors on the Kangra temples. Also, the major architectural elements of which the facade was composed of are widely identical, e.g. the design of the aedicules and niches. But otherwise there are significant differences. These differences primarily result from the fact that the Kangra temples had flat pyramidal roofs – not to be compared to the śikhara-like but pyramidal design of some small Chamba temples such as the temple near the Court (November 11th 2022 entry) or the pyramidal temple in Chauntra (forthcoming). The technology of the almost flat roof structure demanded a square plan for the large-scale temple. Thus, the first major difference between the Kangra Fort temples and the Chamba temples is the plan lay-out which does not allow the proliferation of the central bhādra field. It is also interesting to note the lack of attention this temple has received. The particularities of its floor plan have not been mentioned and one may suspect that this is because it does not fit into the stereotype categorisation on which previous discussions of temple architecture in the region have been based (s. e.g. Laxman Thakur The Architectural Heritage of Himachal Pradesh) – a categorisation which almost exclusively restricts itself on the counting of proliferations of niches and a widely incomplete listing of elements of the vedibhanda with its horizontal layers of different mouldings, i.e. those lower parts of the buildings that are easily investigated without any further technical efforts (see e.g. Thakur 1996). These purely descriptive lists of elements employ Sanskrit terminology that is problematic since sometimes it is not even confirmed as being original. Such discussions not only have an exclusive character. Above all, they have not yet resulted in substantial understanding of the ideological or functional – functional in a ritual sense – context or explain the architectural complexity of actual nagara temples in the region.

Despite its fragmented state of preservation, the last wall of the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Temple may at least serve as a starting point for a proper architectural discussion.

In accordance with our established workflow, a 3D-model could be generated from a set of photographs that were taken in passing during a short visit in 2016. Based on the model, which clearly shows the recesses and proliferation of the façade, an exact plan was prepared. The drawing now clearly shows how the proportional rhythm was established.

The Kangra temple contrasts the Chamba temples in regard to the structural and proportional design of the façade. While the elevation of all the larger Chamba temples have two-partite jaṅghās (façade of the chamber where the niches are placed) above the vedibhanda, the Kangra temple has three. The demand for an additional layer results from the central aedicule (i.e. the proliferating high-relief temple structure in the central field termed A (bhādra) in the elevation drawing). In the nagara architecture of Chamba, the central aedicule extends into the śikhara tower. Such extension is impossible in the case of a flat roof which is why the Kangra temple has three jaṅghās. Because of curvilinear shape of the śikhara, the available spaces on both sides of the amalaka and final were used for the implementation of two small aedicules.

The flanking fields (B-left and B-right) display aedicule which expand over two fields only. The third, top field was split into two and dedicated to two smaller aedicules.

The outer flanking jaṅghā field was clearly divided into three fields and display a vertical line of three aedicules.

The three jaṅghā levels are of different height, diminishing from bottom towards the top. To archive that, the number of layers of two elements of the pilaster structure was changed, to be more precise: the shaft rising from the bottom base-element bearing the vase-of-abundance motif. On the lower jaṅghā, the shaft measures three layers, then two in the middle and finally just one on top (indicated by colours in the bars on the left side of the drawing). One interesting feature concerns the cornice element which is found above the first jaṅghā but missing above the second.

A strange abnormity is the non-symmetric design of the two large aedicule of B-left and B-right, as well as the aedicule of the middle fields of the outer jaṅghā s (C-J2, left and right). In both cases, there is a difference in height of exactly one horizontal layer of brickwork. In addition, the C-J2 aedicule to the right has the cornice that is missing elsewhere on this level. Non-symmetry along the main axis of a temple – which is the case here since this was the rear wall – is usually a no-go in nagara architecture. This leads to the question about the reason for this abnormality. If the design is original, then it would hint at two workshops working on the same wall without proper coordination of works. Otherwise, the a-symmetry might also result from repair works carried out after the earthquake, i.e. a composition of re-used elements. It is not possible to answer this question from afar. Nevertheless, a careful study of the material data can at least lead to questions which might direct attention to the crucial aspects of the ruin and finally lead to a better understanding of the architectural history of these temples.

Images:

References:

Vogel, J.Ph. (1909) Ancient Monuments of Kangra Ruined in the Earthquake. In Archaeological Survey of India Annual Report 1905-6, 10-27, Calcutta.

06.03.2023 – Neil Howard and his work on fortifications in the Western Himalayan Region: A tribute

© Gerald Kozicz – Fortification of Nurpur, Kangra, India, 2016

Summary:

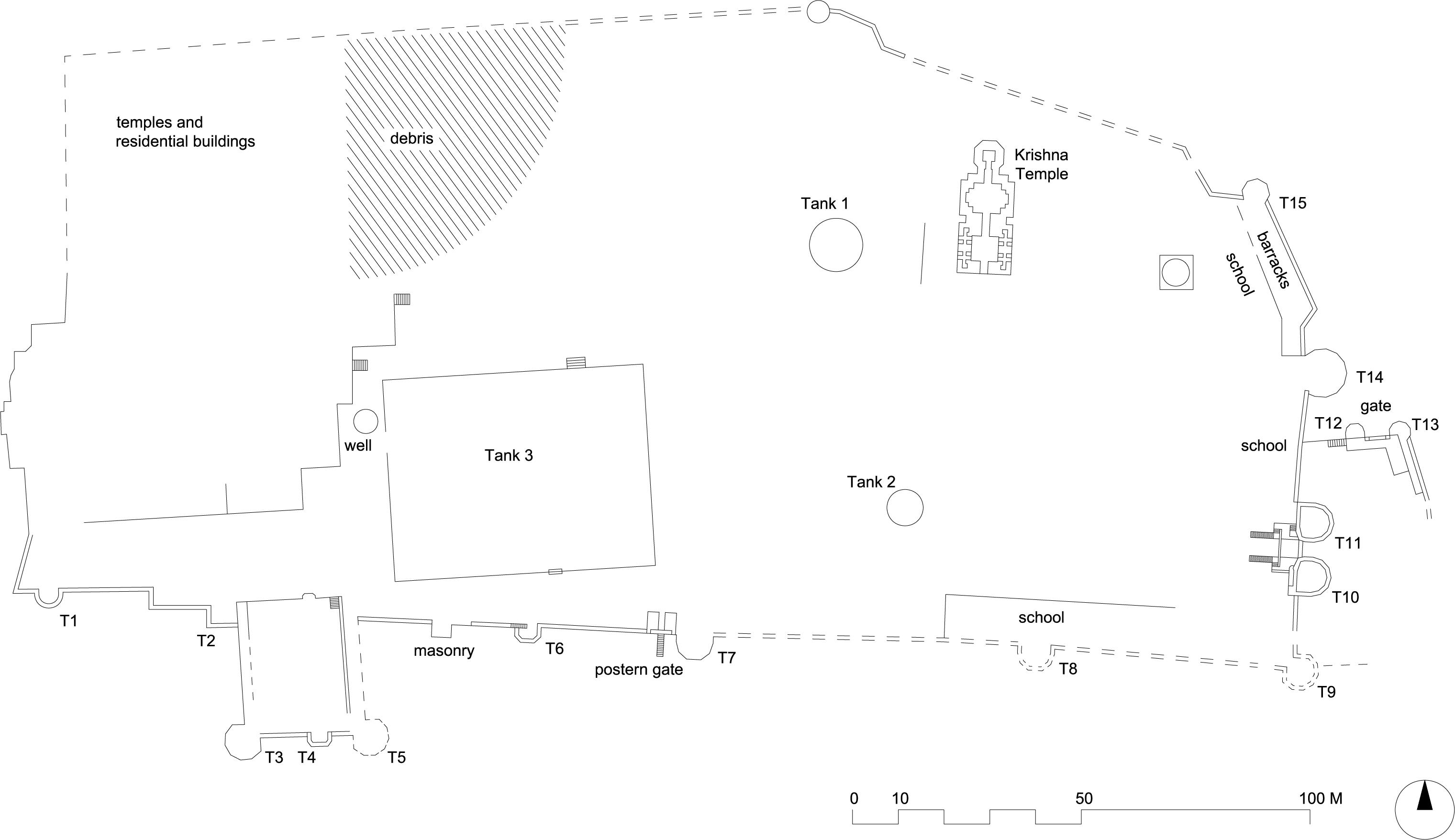

Neil Howard passed away in January 2023. He was a civil engineer by training. When trekking the Western Himalayas with his wife Kath in the early 1980ies, they became deeply fascinated by the rich cultural history of the region. Coming from outside the classical fields related to Himalayan studies (such as religious studies, linguistics, art history or Tibetan and Indian studies), they selected their own topics of research. While Kath focused on the early stupas of Ladakh and produced a seminal paper on the stupas (chörten, mChod-rten) of Ladakh, Neil immediately focused on the fortifications and castles. This topic was to become his academic mission in a way, as his interest would persist throughout his life. It made him the outstanding expert in the field, in particular in the region of Ladakh, and his results got soon published in an extensive article in East&West. Both Kath and Neil decided for specific premises during their fieldwork, one of which was communication. Their works were based on long-lasting relations with local experts and scholars, open-mindedness and kindness, always seeking constructive discussions and willing to share their material. Neil’s interest was not only the local fortresses of Ladakh, but also the military camps of the Dogra’s who invaded Ladakh in the middle of the 19th century and whose camps he accurately tried to trace. Less known is Neil’s research on military structures and fortifications outside Ladakh such as the fortified camps erected by the Gurkhas during their campaigns into the Himachal region. He also did field research on the fortresses of the local kings in Himachal. One fortress he was particularly attracted to was the ruined fort of Nurpur, a fortified royal palace in Kangra, that had been in use as a fortification until the 19th century. Neil spent more than a week at the site, studying the remains of the broken and dilapidated walls and towers when the place had partly been turned into a school yard and park for the local people of the small adjacent villages. Neil took measurements by pacing the rocky area – a method he was well aware of as neither being highly accurate nor time efficient. While generally he used this method as a measurement, for single smaller objects, like towers, he took a more precise approach and used a scale. He basically decided to use whatever worked best under the given circumstances.

In 2013, Neil forwarded his notes to me with the request for a digital site sketch map. This map was meant to be incorporated into a paper on the Nurpur Fort which he was going to write. Neil particularly focused on the southern part of the fortification walls since the northern and western sections were well protected by steep cliffs overlooking the Jabhar Khud, a tributary to the Chakki River, that runs east-to-west north of the rocky spur on which the fort was built. The southern and eastern sections were thus the strongest fortified, and this is also where the gates had been erected. The other remains and ruins along the plateau were of lesser interest to him, which is why he marked the areas of the plateau where there are still remains of palace architecture simply as “debris”.

Neil’s paper addressed an unusual subject and it turned out difficult to find a journal that would accept such a topic which was definitely outside the mainstream. This paper never got published and Neil’s work on Nurpur has never been made accessible. The map based on Neil’s notes might not meet up with modern standards of cartography, but his observations on the castle reflect expertise and a deep understanding of the functional logic behind military structures. His original field research is unique – and the architectural evidence might have faded away in the meantime. This makes his notes an invaluable contribution to the studies of the cultural heritage of Himachal.

Neil Howard was a true British gentleman scholar with a good sense of British humour, a highly respected colleague and a wonderful host to everyone who visited him and his wife and collaborator Kath at their home in Birmingham. An appreciation by John Bray is also accessible at the Ladakh Studies website.

Images:

References:

Howard, Neil (1989) “The Development of the Fortresses of Ladakh c. 950to c.1650 A.D.”East & West 39, no. 1-4, 217-288.

Howard, Kath (1995) “Archaeological Notes on mChod-rten in Ladakh and Zanskar from the 11th-15th Centuries”. In Osmaston, Henry and Philip Kenwood (eds.) Recent Research on Ladakh 4&5, 61-68. London: SOAS Studies.

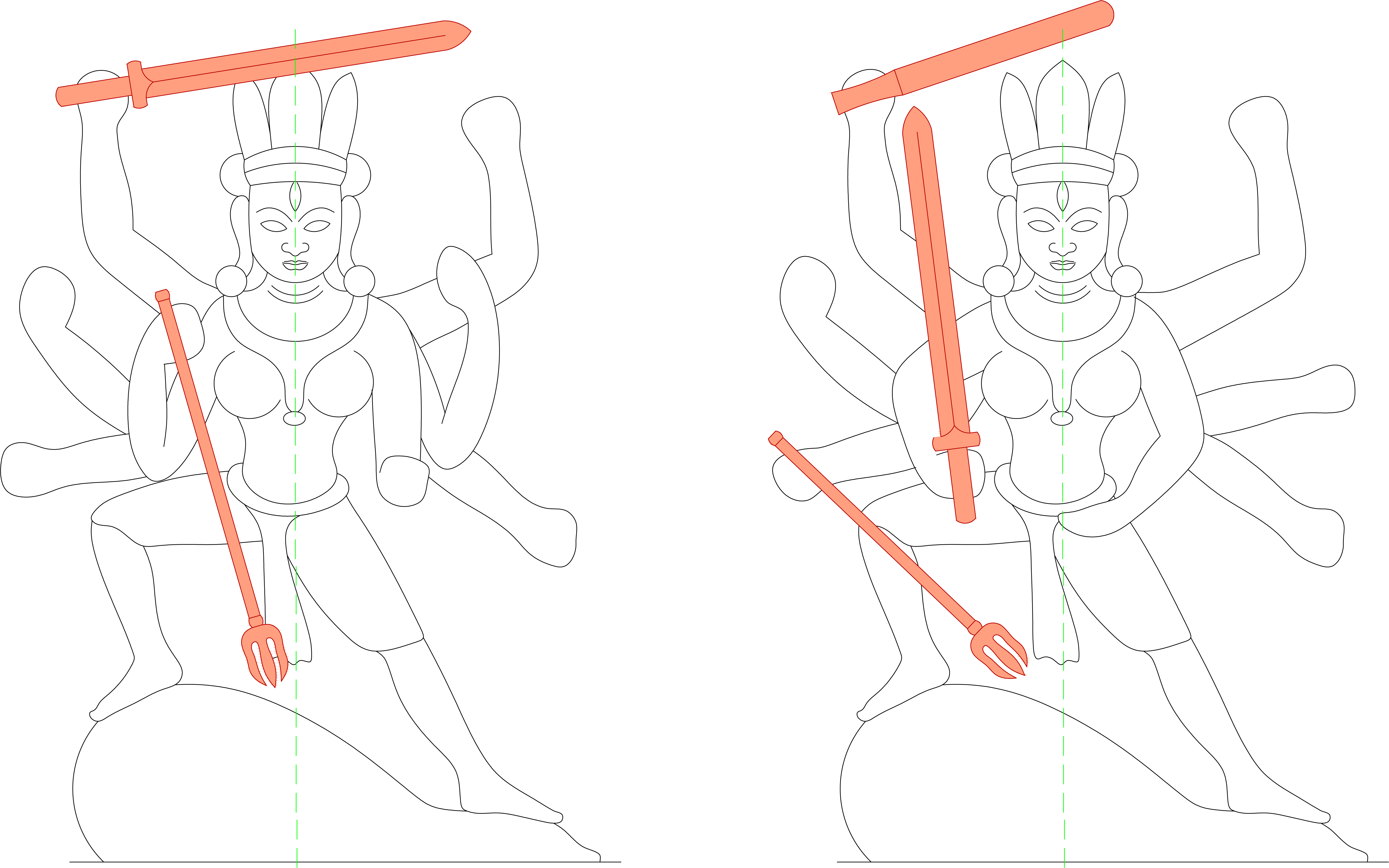

27.02.2023 – The Inner Portal of the Śaktidevī Temple of Chatrarhi:

A Critical Note on Methodology of Field Research:

© Gerald Kozicz – Inner portal of the Śaktidevī Temple of Chatrari, Chamba, India, 2019

Summary:

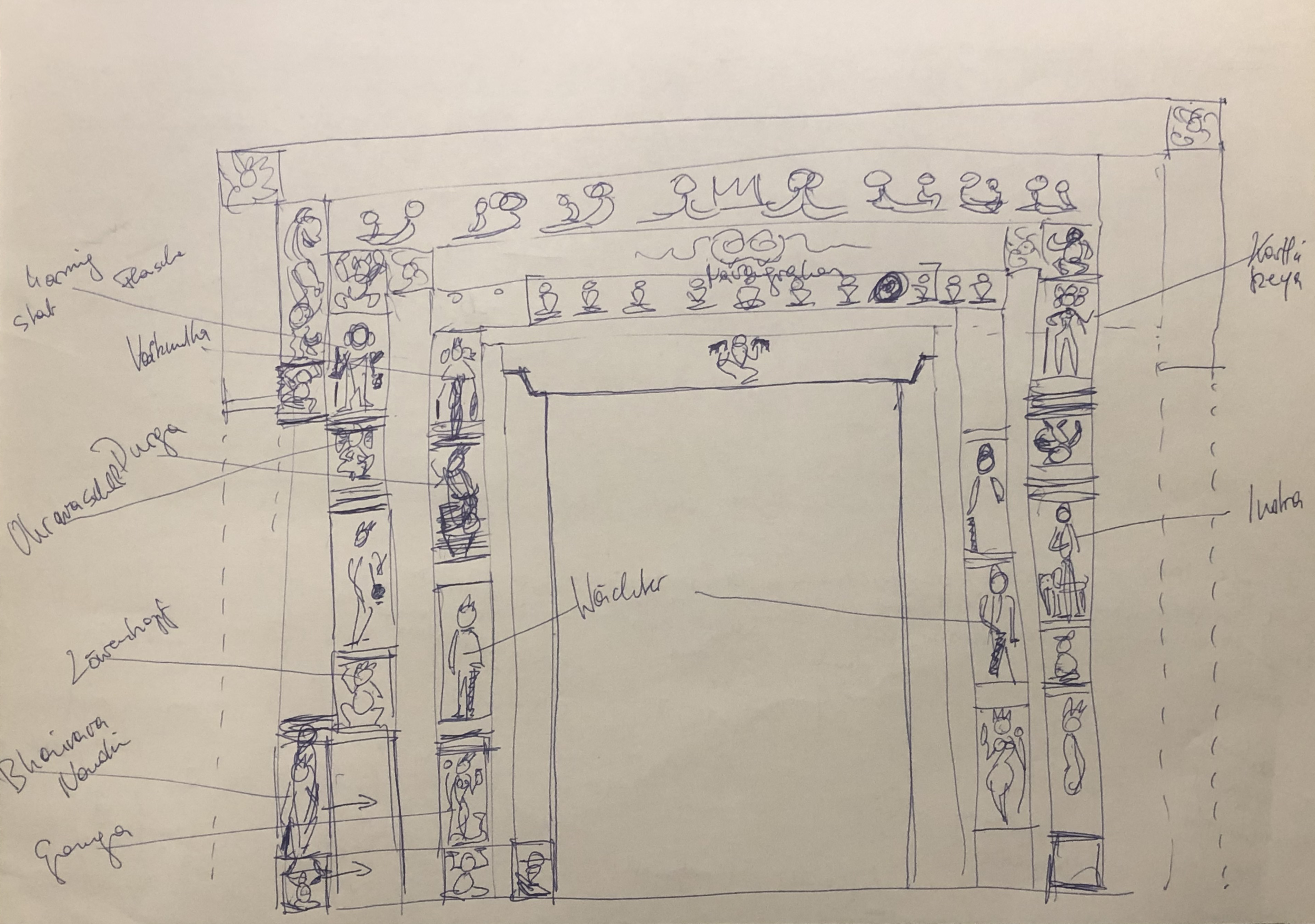

Besides the inner portal of the Lakṣaṇā Devī Temple of Brahmapura, the inner portal of the Śaktidevī Temple of Chatrarhi is the second original wooden doorframe from the very early phase. Dated to the ca. 8th century, the Chatrarhi portal displays close similarities with the outer portal of the Brahmapura Devi Temple regarding composition, style and construction methods. This entry however, is not about the art historical relevance of the portal itself, but rather about its historic discussion as an academic subject.

Chatrarhi itself is a place not easy to get to today. It lies half way between Brahmapura and Chamba Town and to get there one has to take a single lane road that climbs along the steep slopes from the Ravi ravine to the small plateau where the hamlet and its compound are located. Climatic conditions – monsoon in summer and snow in winter – and landslides make travel impossible during most time of the year, which is just one reason why this temple has not yet been surveyed completely. Whoever wants to study its architecture and art but has no chance to see the site itself naturally has to rely on publications as it is the common practice in such case. This is of course academic practice, but the Chatrarhi portal may serve as a useful example to exemplify some critical issues that come with that – issues that become very obvious when one examines some of the previous discussions of this masterpiece in detail.

The first study that appears as a comprehensive discussion of the portal was done by Hermann Goetz and published in his The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba (1955: 87), a publication referred to regularly in every major publication on the art and architecture of Chamba. Goetz begins his discussion of the multi-layered frame from the outward jamb towards the opening but provides no number of the frames but just mentions “the next frame”. He mentions three standing deities on each of the outer jambs plus kneeling gaṇas in minor compartments that separate these four fields (which would be the second layer). He identifies Karttikeya, Indra and (tentatively) Śiva on “the left side” and “Brahmā on the right side”. Now this is correct if the portal is viewed from the perspective of Devī, i.e., from the innermost sanctum. For the viewer’s perspective, Brahmā is on the left and the previously mentioned deities are on the left, i.e., the directions are reversed. No other deities are mentioned on “the right side” here. No position is given for the four deities noted, i.e., the reader is not provided with any information about at which level the deities are positioned and who mirrors whom. Ignoring the “next” jamb which displays ornamental imagery, Goetz immediately continues with the no.4 pair of jambs which contain four standing deities each. He starts on the left jamb at the bottom and identifies the three figures as (tentatively) Vāju or Yama, Durgā Mahiśamardanī and Viṣṇu. Goetz writes that he starts from the bottom, but the figure of Gaṅgā, the River Goddess is then mentioned to be placed below the three deities mentioned above – i.e., Goetz contradicts his own descriptive structure. But what is even worse and more confusing is the fact that this jamb, labelled as “on the left” is at the same side as the outer jamb displaying Brahmā – previously labeled “at the right side”. Goetz changes the perspective – or more likely just confuses right and left. Then Goetz continues on “the right side” and lists “an unidentified goddess(?), a god with a club (Bhairava?), again a god or goddess, and finally the river goddess Yamunā”. One may conclude that the mention of Yamunā at the end points at a list top to bottom, but actually one cannot be sure since the order was confused on the opposite side as well. The publication does not provide any photographs.

A comparatively clear photograph of the portal is provided by Postel, Neven and Mankodi in their “Antiquities of Himachal” (1985: 45-46, fig. 45 and 48). Unfortunately, the left (viewer’s perspective) jambs are not depicted and the details are naturally hardly visible in the total image. The authors provide the exact number of jambs and lintels. They mention Gaṅgā and Yamunā on the “third band” and one may conclude from that – with the help of the photograph – that they start their counting from inside towards the outside. “On the left” they further note Viṣṇu Caturārana, under him Mahiśamardanī followed by a two-armed deity with a ringed club. They hesitate to suggest identifications for the damaged figures on the opposite side. The figures on the outer figurative jamb which would be the “fifth band” do not find any mention in their description, leaving the discussion incomplete. Due to this unexpected omission, the mistake made by Goetz remains undisputed.

Cinzia Pieruccini, who discusses the portals of the Laksanadevi Temple of Brahmapura extensively and with great detail, uses the Chatrarhi Temple as the major comparative monument. Unfortunately, when it comes to the portal she confines her discussion to style, e.g., by comparing the “lions” (1997: 217), and completely avoids the topic of iconography and composition. This is actually surprising since she does not avoid that topic in her discussion of the outer Brahmapura portal. Thus, Goetz’s analysis remains unquestioned once more.

O.C. Handa provides another contribution to the discussion. His study is published twice at least – almost verbatim – in his Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples (2001: 165-66, pl. 22) and Ancient Monuments of Himachal Pradesh (2010: 54-55, pl. 12). His description of the jambs of the six-layered frame starts from the outside towards the inside. He begins with (o)n the left vertical, from bottom upwards are Karttikeya, with six faces and peacock; Indra; and possibly Shiva with his mount, according to Goetz (2001: 165). He next mentions Brahmā on the “right” side. But then he continues with the “left” side where he locates Gaṅgā, Yama (or Bhairava), Durgā and Vaikuṇṭha from bottom to top correctly. This exactly reflects Goetz*s confusion of the orientation. This is also striking because Karttikeya‘s six heads are among the very few details of all the imagery along the whole frame that can be identified even on the low-quality reproduced images of the frame – and these six heads are not with the bottom figure but the top figure of this element as can be clearly be seen on the photograph (2001, pl. 22) in the same publication – which shows the figure on the right side (viewer‘s perspective). It must also be recalled that Goetz does not provide the vertical order as quoted by Handa. For the inner element with the figurative imagery Handa follows Goetz’s switch of perspective. Handa still provides a few new details such as the Viṣṇu Vaikuṇṭha, previously termed Viṣṇu Caturārana by Postel, Neven and Mankodi. Such identification should be the result of his in-situ inspection – which triggers the question why in his published study the mistake made by Goetz is not critically reviewed and corrected.

Finally, Sangram Singh in his The Art of Mountain Temples (2015: 118-22) provides a clear, well-structured discussion of the portal. The reader is well guided through the complex six-layered composition which is described in detail layer by layer. Singh maintains a clear orientation keeping “right and left” constantly in accordance with the viewer’s perspective. He also contributes to the discussion by suggesting the tentative identification of the two decayed figures as forms of Viṣṇu.

To sum up, the discussion by Sangram Singh provides us with a solid description of the portal’s jambs as complete as possible given the state of preservation. But this not yet brings the discussion to a satisfying end, as a few questions now arise. How is it possible to ascertain that Singh is correct? Unfortunately, the reproductions of his photographs (ibid: 204-205, pl. 6.10 – 6.13) are rather poor and the identification of details almost impossible. He also avoids mention of the confused orientation found in all previous publications noticed above. It is impossible for a reader who is without a proper personal documentation at hand, to evaluate the correctness of each author. It is also important to ask now whether it was the status of “Godfather of Chamba temple studies” held by Goetz that hampered critical approaches towards his work?

Whatever the reason, this blog entry provides some material that will support the analysis by Sangram Singh. The visual material is confined to the jambs so far and will be completed at a later point.

The reader of this present summary of earlier publications might easily get the impression that this entry is about criticising or even dismantling the fame of Hermann Goetz. This is actually not the case in the first place. The actual topic is the question: How could such mistake happen – and how could it have been avoided or corrected properly?

First of all – and this is critical after all – the description by Goetz as such is confusing even where the directions are correct. But then, how did the mistake happen in practice? And why did no one notice the mistake and correct it? Both questions are related to a single problem and this is viral: Historians – including art historians – do not sketch. Everyone makes mistakes. But such mistakes do not remain unnoticed while sketching. This process of reproduction means permanent interaction between draughtsman and object – be it a stele, an interior space, an architectural object or even a landscape. This interaction is a slow-motion process of appropriation of the qualities of the object through the capturing of the significant features on paper. It is a permanent process of filtering, evaluation, perception of structure – a method of understanding that cannot be replaced by photographs or textual notes. Mistakes on the paper become immediately apparent and trigger corrections. Sketches are reflections of a cognitive process – and as such they also work as media to convey the result of a survey to the reader. They are not perfect in a technical sense like a photograph. But sketches are visual studies and they have the potential to communicate the result directly.

Trying to understand and creating a picture of the whole – both metaphorically as well as visually – from Goetz’s description is a frustrating process that does not yield any useful result. A simple sketch would be of tremendous help. And if Goetz would have produced one, he would probably have realized his mistake immediately and provided all following researchers with a correct and solid basis for further studies. Even Singh’s analysis can only be properly understood and appreciated if one produces a sketch from his notes. Otherwise, the complexity of the door frame is almost impossible to imagine.

This blog is of course primarily dedicated to digital media and methods of presentation of the cultural heritage of the Himalayan region. However, the sketch is at the very beginning of this process which starts with field research and documentation.

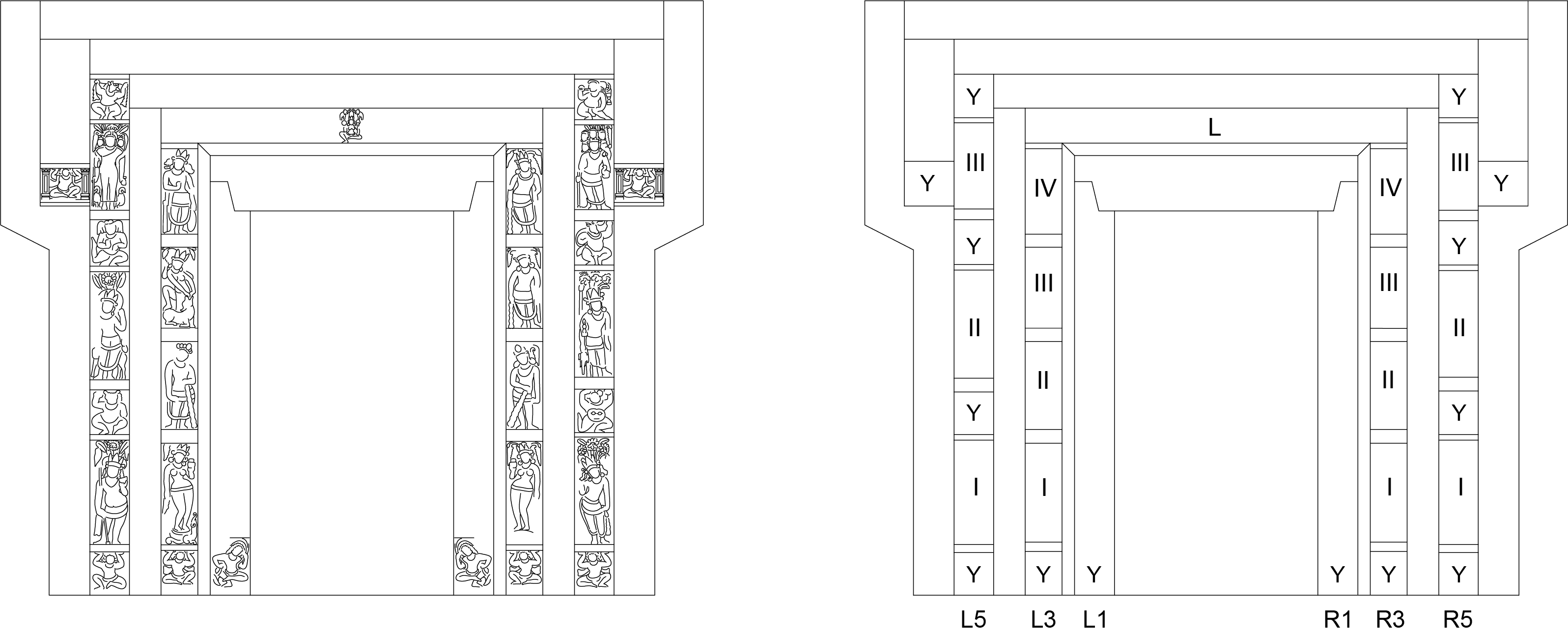

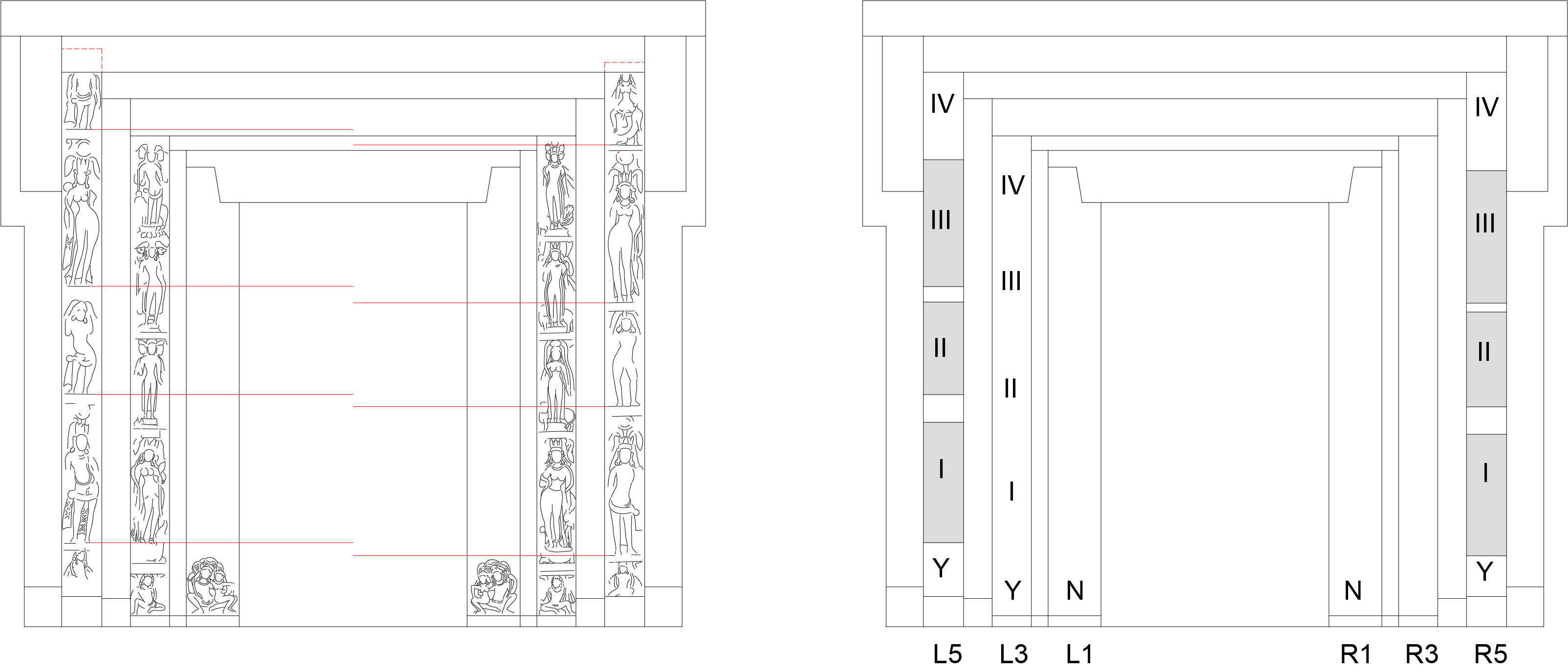

© Gerald Kozicz – Line drawing of the deities along the jambs plus the figure of Lakṣmī in the lalatabimba of the first lintel, Graz, Austria, 2023

L: Lakṣmī

L3-I: Gaṅgā

L3-II: Bhairava(?)

L3-III: Mahiśamardanī

L3-IV: Vaikuṇṭha

L5-I: Yama(?)

L5-II: Śiva(?)

L5-III: Brahmā

R3-I: Yamunā

R3-II: Nandin(?)

R3-III: Deity with club (Viṣṇu?)

R3-IV: Deity with club (Viṣṇu?)

R5-1: Maheśvara (?)

R5-II: Indra

R5-III: Karttikeya

Images:

References:

Goetz, H. (1955) The Early Wooden Temples of Chamba. Brill, Leiden.

Handa, O.C. (2001) Temple Architecture of the Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Indus Publication, New Delhi.

Handa O.C. (2010) Ancient Monuments of Himachal Pradesh. Museum of Kangra Art, Dharamshala.

Singh, Sangram (2015) The Art of Mountain Temples. Agam Kala Prakshan, Delhi.

Pieruccini, C. (1997) ‘The Temple of Laksana Devi at Bharmaur’, East and West 47, nos. 1–4, 171–228.

20.02.2023 – Orphaned Objects 2:

A collection of stone works assembled in the Chatrarhi courtyard:

© Gerald Kozicz – Courtyard of the compound of Chatrarhi, Chamba, India, 2016

Summary:

The significance of the courtyard of Chatrarhi Temple complex has widely been overshadowed by the main sanctum of the compound with its wooden architecture and the main idol of the goddess inside. The courtyard appears rather insuspicious on first sight. What appears unusual is the different level of the courtyard area. While the temple itself is on roughle the same level as the surrounding open space, one has to descend to a lower level in front of the temple in order to climb some stairs again to reach the outer portal.

On the opposite side of the lower terrain, a platform was erected. On the platform and facing the sanctum, a bull is placed in the most prominent position. This sculpture is certainly of an early age. It may hower be doubted that is is original since the appropriate vahana (animal mount) in front of a Devī temple would be the lion.

Otherwise, the platform has become another collecting point for orphaned stone images. these images are quite randomly arranged. They include several lingams and curvilinear-shaped cones, a kind of saurapīṭha slap centering on a lotus flower with a goose having a pearl-chain in its beak, and several steles from different periods. One figure literally stands out from the collection. It is a standing figure of a male holding a spear in the right hand. The figure has a large circular halo that shields half of its back. The style reminds on the two dvārapālas (door-keepers) of Lākhamaṇḍal discussed by T.S. Maxwell (1980:15-18, fig.4 and 5) and dated on stylistic grounds to the 7th-8th century, i.e., the post-Gupta era. The figur at Chatrarhi differs from the Lākhamaṇḍal sculptures since they lack the halo and lean against clubs. The halo hints at a deity and the spear are the major attribute of Skanda-Kārttikeya/Kumara, the warrior god of the Brahmanic pantheon and son of Śiva. The muscular chest and the posture with the left hand on the waistband mirror images of this deity elsewhere, e.g., the two-armed Skanda from Apsidal (Rangarajan2010, Fig. 39). Still, there are several features that would be expected with a depiction of the warrior god which are absent from this stele. First of all, Kārttikeya‘s animal mount, the peacock, is not depicted. The bird is usually depicted behind the legs of the deity when standing or under the deity when seated. In this case, the deity is just standing on a square pedestal. Second, Skanda-Kumara’s typical hair-do that mimics the two horns of the ram, are also absent. Instead, the figure wears a bejewelled hat-crown. Finally, the necklace of tiger-claws that is sometimes worn by Kārttikeya is not there, either. Still, what is depicted in this stele clearly hints at Skanda-Kārttikeya/Kumara. Even if the figure would display a different deity or semi-god, its art historical significance would not drop. This stele is among the oldest stone steles of this part of the Western Himalayan Hills, if not the oldest.

Images:

References:

Maxwell, T. S. (1980) ˋLākhamaṇḍal and Triloknāth: The Transformed Functions of Hindu Architecture in Two Cross-cultural Zones of the Western Himalayasʻ. In Art International, Volume XXIV/1-2, 9-74.

Rangarajan, H. (2010) Images of Skanda-Kārttikeya-Murugan: An Iconographic Study. Sharada Publishing House, Delhi.

13.02.2023 – Dressed with Conches: Attire unique to the Ears of Gaṇeśa:

© Gerald Kozicz – Gaṇeśa of the Baśeśvara temple of Bajaura, Kulu, India, 2017

Summary:

While attributes and physical aspects such as body colour, number of arms and heads as well as postures and mudras may be considered the major categories of visual language in Indian iconography – Hindu/Brahmanic, Buddhist and Jain – there are also minor elements which are distinctive and may refer to specific groups or even individual deities or demi-gods. These include certain dresses but also jewelry and attire. The necklace of claws worn by Skanda/Kumara/Kārttikeya and also by the Buddhist bodhisattva Manjusri is a prominent example.

This entry addresses a tiny detail in the iconography of Gaṇeśa, a detail which is connected to the ears of the elephant-headed god and thus related to his specific physiognomy. It is a pair of conches that hang right in front of the opening to the ear canal. It is the visual similarity between the shape of the conch and this part of the human ear that has resulted in the term „Ohr-Muschel“ (lit. „ear-conch“) in German, and thus catches attention especially by a someone speaking German. These conches do not appear in every depiction of Gaṇeśa. Since the conches constitute for quite a tiny part of the god’s attire, they can not be shown in small sculptures or carvings but only represented within large-scale works. In Chamba, they have so far only been detected on the Gaṇeśa stele embedded in the compound wall of Swai. They are also found on steles of Gaṇeśa in neighbouring regions. One such example is the well-known Gaṇeśa enshrined in the southern chamber of the Baśeśvara temple of Bajaura in Kulu to the east of Chamba. Another, further to the South-East but still in Himachal, is the Gaṇeśa in the southern niche of the Temple III at Parahat near Hatkoti, a Śiva temple that clearly displays post-Gupta stilistic elements and may be approximately dated to the 8th century. The conches as elements of Gaṇeśa’s jewelry are not limited to North-West India. Several specimens are now in various museums in Bangladesh and published in Sculptures from Bangladesh (Haque and Gail 2008: 516-520, Pls. 432, 435, 436, 44 and 446). The catalogue entries however do not make any reference to the conches.

The wide-spread appearence of the conch-jewelry signals a well-established practise but does not yet inform us about a specific meanic or symbolism of these tiny members of the iconographic programme. Did they have any meaning at all? Or was it just convenient to place them there – a matter of visual relation between physiognomy and shape, which in turn invited their inclusion? The conch is otherwise clearly related with Viṣṇu and also with Durgā, who receives the weapons from all the male gods when she sets out to fight the asura armies. The conch (śanka) also forms a pair with the lotus (padma) as niddhi (little treasure), i.e. Śankaniddhi and Padmaniddhi. A connection with niddhi symbolism appears far-fetched for the ear jewelry but can not be completely ruled out since Gaṇeśa is also related to aspects of abundance and wealth.

For the time being, the pair of conches as attire to the ears of Gaṇeśa may be considered a secondary element of the god’s iconography that was known across all over Northern India at least.

Images:

References:

Haque, Enamul and Adalbert Gail (ed.): “Sculptures in Bangladesh”. The International Centre for Study of Bengal Art, Dhaka (2008)

06.02.2023 – Orphaned objects 1: Four Gaṇeśa steles and one broken Durgā:

© Gerald Kozicz – Gaṇeśa Mahiśāsuramardanī at the Lakṣaṇā Devī Temple of Brahmapura, Chamba, India, 2019

Summary:

The term “orphaned” has been coined to define the decontextualized status of a cultural object, mainly in the field of museology when the provenance or original setting to which an object once belong is unknown (Motoh, forthcoming). It appears however, also as a perfect term to describe the situation all over Northern India where steles and sculptures have been removed from broken temples the traces of which have sometimes completely disappeared. Little information is sometimes available about the history of single objects, where steles and sculptures had been originally placed, which configuration they had been part of, where they had actually even come from exactly. Very often, for example, when temples collapse or when stone steles simply resurface from the ground in the course of construction activities, these steles are either arranged under sacred trees or simply taken to the next intact temple and enshrined either in the sanctum or one of the bhadra niches. Sacred trees are also inside temple compounds, and many temple complexes have thus become hoards of orphaned steles. Many of these steles show severe traces of decay and have often escaped scholarly attention.

One such example is the Gaṇeśa inside the Gauriśankara Temple of Chatrarhi where the stele of the elephant-headed god is placed against the left side wall (viewer’s perspective from the entrance). The four-armed deity is partly covered by a textile and shows quite some traces of abrasion. Another Gaṇeśa stele is placed inside the Śiva temple of Swai. The stele is not as fine as the Gaṇeśa stele embedded in the courtyard wall (see the 01.08.2022 entry). The elephant-headed son of Śiva and Pārvatī is four-armed, holding axe and radish in the right hands, and a cup with sweets and a lotus(?) in the left hands. His head is decorated with an orange flower – and a flower is also carved above his head into the large round backslab (nimbus?), just like the flower above the head of the Gaṇeśa outside. In a comparatively poor state of preservation is the Gaṇeśa inside the Lakṣaṇā Devī Temple of Brahmapura. The god is again shown four-armed. At least the axe and the sweets can be identified with certainty. This stele is placed next to a broken stele showing Mahiśāsuramardanī. This image of Durgā differs from the larger steles presented in the previous entries since it shows the deity with the right foot on the demon’s bull head and grabbing the tail, thereby lifting the demon’s body. Both the steles show clear remains of orange colour.

Touching the foreheads of deities, the attributes and the breasts in the case of female deities is an act of religious veneration in daily ritual. However, in the case of Gaṇeśa the application of orange colour all over the body seems to have been an old tradition. With new paints available on the marked this tradition has however caused quite some damage to stone sculptures. Another modern fashion is the application of silver plates on the eyes – a fashion that is not yet that popular in Chamba as it is in other regions of India such as Bihar. A rare example from Chamba is the four-armed Gaṇeśa inside the dilapidated nagara shrine of Rajnagar.

The application of orange paint on Gaṇeśa images is also eye-catching on door frames. It is a regular feature since Gaṇeśa is in the central position of the first lintel of almost every temple affiliated with the cult of Śiva and Pārvatī. Even inside the Lakṣmī-Nārāyaṇa Complex, the steles of Gaṇeśa have been covered with thick layers of paint. These layers sometimes even completely mantle the details of the iconography of the respective figure and the identification of a Gaṇeśa is only possible through the shape of the head and the trunk.

Images:

References:

Motoh, Helena (forthcoming) Orphan(ed) Scroll: the Case of Contextualizing a Late Qing Object in a Slovenian Museum. In Ming Qing Yanjiu 24 (2020) 139–158.

30.01.2023 – Kangra, Kulu and Shimla – Regions category added:

This weeks update sheds some light on the geographical situation as well as the correlation between the different regions existing along the southern face of the Himalayan chain. The newly added Regions category is meant to provide an overview of the different regions discussed in this blog and serve as a guide for our visitors accross the different topics and articles discussed on this website.

The new category can either be found by clicking on it in the top menu or directly by clicking HERE

Kangra – a hub for the transmission of the artistic tradition of Mughal art:

© Gerald Kozicz – Kangra, India, 2018

Summary: