Nagara Achitecture

Nagara temple architecture reflects the idea of the house as both a physical shelter for a specific deity or its symbolic representation, and the manifestation of the cosmological dimension through geometry and visual art. Nagara temple architecture is based on a number of major design principles which are shared by all temples and a number of minor principles which depend on regional factors or sub-categories based on size.

The fundamental principles shared by all the temples under discussion, is the centric conception. The nagara temple is based on a cartesian system. All its three major parts, i.e. the pedestal, the sanctum and the tower “emerge” from a basic square. The over-all form develops around the central vertical axis. All the temples dealt with in the region of the Western Himalayan foot hills were built from stone as this material is available in abundance. Due to its durability, dressed stone also allowed for the representation of a complex system of formal elements, decorative patterns and iconographical content all over the outer surface. The result is a superimposition of architectural form and visual narrative through which architecture becomes object and vice versa – a visual system which seems to complete the central deity rather than simple cover it. The aspect of centrality is enhanced by the various floor plans of temples which reflect patterns similar to mandala grids.

As one of the directions of the square plan had to be used for the entrance, the ideal four-fold – or five-fold in case the vertical axis is also counted – system had to be turned into a single symmetric plan. Double-symmetry could only be realized above the portal along the iconic curvilinear tower called shikara. Although the shikara tower is the dominating member of the over-all form, it is the portal that is of major importance. The portal, in particular the actual doorframe, is the condensed depiction of the essence of the deity and the doctrinal concept – and at the same time it forms the actual frame for the representation of the respective deity that is placed inside the otherwise empty and widely undecorated sanctum called garbhagriha.

It may be noted that the nagara temples of the region under discussion, are comparatively small monuments regarding the size of the cella. Even the large monuments do not allow for gatherings inside their sanctums. Most temples only allow the priest (pujari) and one devotee inside the chamber at the same time. Smaller monuments – sometimes measuring less than 2m from bottom to top - are even inaccessible.

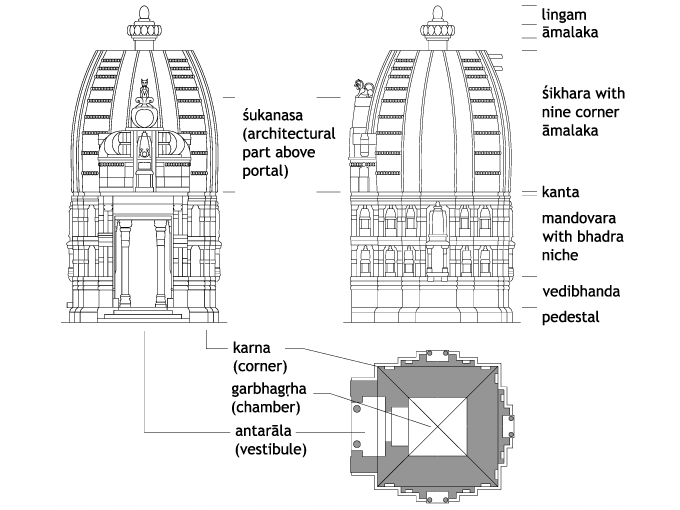

Naturally, the discussion of Indian architecture can not be done without the classical terminology which is of course in Sanskrit. However, regional differences as well as inconsistency in literature have so far hampered the establishment of a unified terminological system. For the sake of users who are neither familiar with this type of architecture nor Sanskrit, this introduction includes a diagrammatic plan of a nagara temple, the Gaurishankar Temple of Dashal in Kullu Valley, which displays the major parts and elements as used for this project. While the diagramme gives the terms with diacritics, the westernized transliteration, i.e. the form without diacritics, is used in the other textual parts.

Shiva shrine, Naggar

Besides the well-known Gauri Shankar Temple and the adjacent smaller nagara shrine right below the Naggar Castle, the village of Naggar is the home of another group of early stone shrines. This complex has almost completely escaped scholarly attention as it is located behind an agglomeration of farm houses and out of sight from the village road. The setting consists of two nagara shrines, one of which is dedicated to Ganesha and the other one dedicated to Shiva. In addition, a small altar was erected in the open. On the altar we find a small stele of Surya, the Sun-God. Right behind the stele red ribbons tied around a tree signify the sanctity of that place. All the three elements of the site face the western direction, i.e. the valley. Regarding position within the setting, the Shiva Temple is the foremost as it is nearest to the valley. Architecturally speaking, the construction of the shrine is simple and explanatory. Each part of the monument is built of a single stone slab. The pedestal consists of three layers each of which displays a different design, the garbagrha (chamber) is constructed from four slabs each of which builds one of the four walls, and the garbagrha is covered by a single, large slab. The shikara tower again is composed of several large slabs each of which representing one horizontal layer, i.e. the shrine lacks the usual bonding found with larger monuments. The chamber centres on a lingam while the three niches on the outer faces of the monument are dedicated to Brahma (North), Shiva and Parvati (East / rear face) and Vishnu (South).

Gauri Shankar shrine, Jagatsukh

The nagara shrine dedicated to Gauri Shankar (Shiva and Parvati) bears witness of its former political and socio-religious significance. Structural remains and fragments of other temples can be found as re-used members of the new composite temple (made of wood and stone elements) of Sandya Gayatri. The re-used parts of an earlier temple include a door frame with Ganesha in lalatabimba (i.e. the central position on the first lintel). In addition, some carved stone slabs depicting ornamental or iconographic motifs, and structural elements such as pillars of bhadra niches (central niches of projecting fields along the cardinal directions or axis of a temple’s main body). Fragments of another temple portal are arranged in the courtyards in the front of that temple. Fragments of a small shrine are assembled on both sides of the gate to the courtyards wall. That small box-like shrine is dedicated to an image of Ganesha. All the evidence points at a very strong presence of Shivaism in Jagatsukh through all historical periods since the Gauri Shankar Temple may be listed among the earliest surviving temples of the Kullu Valley. It is probably datable to the period when Jagatsukh was the capital. Today, the Gauri Shankar Temple is located at the eastern edge of the public play ground. That playground is surrounded by the Gauri Shankar Temple (East), a huge sacred tree (South), the rear face of the Sandhya Gayatri Temple (West) and a three-story school building (North). The playground is used both by the students as well as by the youths of the village. Remarkably, the permanent activities of all sorts of everyday life do not harm the spiritual atmosphere of the small temple who is sort of supervising the scenery from a platform. A small but constant flux of pilgrims―many of them tourists on their way to Manali―sustains the religious significance of the site.

Gauri Shankar temple, Dashal

The village of Dashal is situated along the ancient route that connects Jagatsukh and Nagar, the old political centres of the Upper Kullu Valley on the left side of the Beas River. It‘s major temple is the Gauri-Shankara Temple. With a total height of about 11.5m it is one of the largest monuments of the valley. It‘s architectural concept is based on a cruciform plan with two projections, i.e. tri-angha, towards the North, East and South. The entrance into the square cella, the garbhagrha, faces the West. A porch or antarala creates a transitional space between the inner-most sanctum and its mundane environment. The major architectural parts of the structure are the pedestal of the temple, the corpus of the actual sanctum, the curvilinear shikara tower with its amalaka on top as well as the attached shukanasa, the iconic frontal part that rests on porch. Regarding its over-all proportional and configurational aspects as well as its theological affiliation it resembles the Gauri-Shankara Temple of Naggar. That later temple which is situated below Naggar Castle has been dated to the twelve century by Laxman Thakur. However, the quality of the carvings of the latter are inferior to those of the Dashal temple. Since a continuous degeneration of craftsmanship from the tenth century onwards can be observed it appears conclusive to place the Gauri-Shankara Temple of Dashal to around 1100 CE.

Basheshara Mahadeva temple, Bajaura

The hamlet of Bajaura is located on the right side of the River Beas in the Kullu Valley. Unlike, Naggar and other places on the left banks of the Beas which are situated on higher levels such as plateaus or along the slopes, Bajaura is almost at same level with the Beas. It is one of the most fruitful parts of the valley and its houses are scattered among orchards and fields. Bajaura is the home of a couple of temples dating from different cultural periods and in its neighbourhood fragments of several broken temples as well various loose artefacts have been documented over the past years. Among those, a set of Yogini sculptures, a Buddha stele and a small mandala-like lingam configuration stand out. Bajaura is best known for the Basheshara Mahadeva Temple, a nagara temple surrounded by fields and reachable only by a small road which is hardly motorable. The monument is of significant age and may be counted among the earliest surviving monuments of the valley together with the shrines of Naggar (Shiva Shrine at Shitala Compound and the shrine near the Gauri-Shankara Temple) and the Jagatsukh Shrine). The entrance of the temple faces the East, i.e. the Beas. In front of it we find a huge sacred tree, which has become the centre of worship on its own right. This is because of its brink which – when the tree got older – gradually developed a relief which recalls the shape of a Ganesha head. This head faces the temple and through this the temple dedicated to Shiva as “Lord of the Universe” (Vishveshvara) and Ganesha, who is the son of Shiva and Parvati, created a unique spatial and sort of “super-sacred sphere”. Today, the temple can be easily reached from the nearby modern highway. The short distance to Kullu Town, the modern district centre, has enhanced its importance as a major destination of pilgrimage.

Gaurishankar Temple and Kali Shrine, Naggar

Naggar is one of the major administrative centres of the Kullu Valley and has been the seat of a local Raja for centuries until the colonial period. Its castle is still the centre of the old town and a number of sanctuaries of different architectural forms and from different eras can be found all over the area. The best known monuments are the large Gaurishankar Temple and a nearby smaller shrine. The latter is locally referred to as Kali Shrine. This small temple does by far not receive the attention by the community and pilgrims which it deserves, probably due to the absence of a proper image inside its chamber. However, as an architectural monument viewed from an academic perspective, this is probably the most important surviving temple datable to the very early period of Brahmanic activities in the western Himalayan foot hills. It resembles the Gaurishankar Shrine of Jagatsukh regarding both the artistic quality and the architectural concept, but when it comes to the complexity of the design of the shikara tower, this temple is unrivalled. The temple is among the category of temples which can not be entered due to the small size of the chamber. Veneration of the sculpture inside, which is in a state of decay and erosion, can only take place from outside. Despite of its bad state of preservation, the image can be identified as Vishnu due to the club and the Garuda as vehicle. As in other cases, there is no proof that the sculpture is original. It is worth noting that the image inside the round medallion of the shukanasa is single-faced and wears a crown which would support a Vaishnava affiliation rather than a Shiva context. On the other hand, the figures in the bhadra niches clearly support a Shaivait context. The temple does have a pranala, but inside the chamber there is an altar – no Shiva lingam.

Shiva Temple, Saura

Saura – nowadays also known as Sarasvatinagar – is a small hamlet south of Hatkoti and on the western bank of Pabbar River, a tributary to Yamuna River. While Hatkoti is a vibrant pilgrimage site, the centre of Saura can not even be reached by a motorable road. A dozen of houses are clustered around a nagara temple of significant age. The temple faces east. It was built on a cruciform plan with three external chambers to the basic cube of the mandovara. All the three extensions were covered by a roof with elegant eaves. As the entrance was through the fourth arm of the cross, this resulted in a sort of long passage into the griha, which could also serve as an inner ante-chamber to the innermost sanctum. Remarkably, the pranala of the temple which seems to be connected to the altar, was built into the southern arm despite. Normally, the northern direction is where the pranala is found unless there is a specific reason for changing this rule. Each external chamber contains a small altar. Today, all chambers and altars are empty. In addition to the entrance passage there is an antarala which rests on the portal and two square coloumns. The same design of the columns can also be found at Parahat north of Hatkoti and on the Rudra-Shiva Temple at Balag.

Shiva Shrine, Balag

The village of Balag is situated in the hills east of Shimla. Its architectural heritage includes two nagara temples of different size. The large temple, dedicated to Rudra –Shiva, has obviously undergone multiple repair and restoration works over the past centuries. Also, a mandapa has been added as well. The original shikara tower is today protected by a sort of pent roof covered with thin stone plates. Such protective measure is rather uncommon for the eastern parts of Himachal Pradesh while it has become a standard feature in temple maintenance in Chamba. The small temple is placed in a modern platform. It faces north. It is a simple design based in a dvi-angha plan. The basic square has been turned into a rectangle as the door frame was placed between two wall elements that project from the kanta elements by ca. 20 cm. The sanctum is still covered by a lantern ceiling composed of “rotating squares”. Inside we find an elaborate altar made of several layers. It is attached to the rear wall and equipped with a pranala towards the East. It may be noted, that the connected pranala that projects from the eastern façade is placed one layer of brickwork below the position of the inner pranala. The temple’s religious history has not yet been firmly attested. The medallion of the shukanasa shows a single head with a crown that would indicate Vishnu or Surya rather than Shiva. However, Ganesha is depicted in the lalatabimba position above the entrance hinting at a Shaiva context. It may also be noted, that the much eroded sculpture on the altar inside the cella has a round emblem in his left hand, possibly a disc – the main weapon of Vishnu – or a lotus flower – the sun symbol of Surya. However, the state of preservation of the sculpture can only be explained by a long period in the open and exposure to wind and weather – and it is therefore impossible to attest its Frajnaoriginal context with this shrine. An indicator for the presence of at least one Vishnu sanctuary in the area was fixed into a modern concrete wall facing the small shrine, namely a shukanasa roundel showing Vishnu and his wife Lakshmi.

Shiva Shrine at Triloknath Compound, Mandi

The city of Mandi is among the old centres of Tantric activities in Western Himalayan Foothills. The Triloknath Compound on the cliffs right above the conflux of the Beas and the Suketi Khad Rivers is probably the most iconic and significant sacred clusters of the area. It consists of a large temple and a number of smaller shrines in various different states of preservation. The mulaprasada of the large temple appears like a simplified version of the Dashal Gaurishankar Temple. It shares the shallow gavaksha pattern all over the shikara tower as well as the relatively small-sized alamaka. The mandapa of the large temple at Triloknath Compound displays a number of features that are alien to nagara architecture further up the Beas River such as vaults and the roof construction made of huge stone plates. Among the smaller monuments, the shrine closest to the modern gate of the compound stands out. Regarding its overall design, it reminds of the Jagatsukh Gaurishankar Temple and the Kali Shrine of Naggar. Unfortunately it was made of soft local stone and many details of its surface design have vanished. It is probably not as old as the Kullu temples, but it is most likely among the oldest surviving monuments of Mandi and datable to the turn of the first millennium.

Vishnu Shrine near the Court, Chamba

Next to the modern District Court Building of Chamba Town stands a small Vishnu Temple. It shares a number of features with the pyramid-like Lakshmi Nath Temple at Chauntra, but its architecture and decoration is more refined. It was built on a square plan. Since the shukanasa of this temple was made larger than the Chauntra structure, additional support was needed. Therefore the entrance façade projects from the basic square – similar to the Honi Mata of Rajnagar – and acts as a load-bearing structural element. Like with most of the other temple which are eka-angha at the mandovara-level, the tower is dvi-angha.

Lakshmi Nath Shrine at Chauntra, Chamba

Chauntra is a quarter of Chamba. It is to the East of the Lakshmi-Narayan Compound and the home of a number of smaller stone temples. Some of the temples are of the classical nagara type while others represent an architectural model different from the usual nagara form. The difference results from the tower. It is not curvilinear but pyramid-like. One of those temples can be found on a large platforFrajm which appears like an open yard between the adjacent multi-storey private houses. It faces north and is dedicated to Vishnu. It is known as Lakshmi Nath Temple and receives regular attention by the local community who venerate the sanctum on a daily basis when passing by. The plan of the temple is eka-angha (square) without proliferations towards the exterior. The cella was covered by a three-level lantern ceiling.

Honi Mata Shrine, Rajnagar

According to local tradition, Rajnagar had been the capital of the Kingdom of Chamba for a short period some centuries ago. The village area covers a wide plateau above Ravi River. Embedded in corn fields, lies a small religious compound. It consists of a larger temple, the structure of which displays an uncommon architectural concept. Its mandovara is a solid stone construction and its entrance faces the East. On top of the mandovara rises a three-storey pagoda-like tower made of stone. Such type of roof was normally a member of a wooden temple and constructed as a wooden structure. A remarkable number of Nandi sculptures, the vahana of Shiva, are seated in line in front of the temple’s porch. They provide some clue of the original number of temples dedicated to Shiva in the area. In addition to the main sanctum there are another two temples of the small category. One shrine is placed behind the main temple and faces the same direction. This shrine is quite dilapidated and its shikara tower is much decayed. However, the Ganesha sculpture inside the small chamber is a remarkable piece of religious art. By contrast, the third temple which is placed to the South of the main temple, faces the opposite direction. According to local tradition it had been transferred to the compound from some other site – just like the Nandi sculptures. This small temple is called Honi Mata. From the architectural perspective its design appears archaic and simple. Still the design displays a number of delicate features. While the mandovara is eka-angha in plan, i.e. without proliferation, the shikara tower is dvi-angha in plan. In order to cover up the proliferation of the roof, the builders introduced an eave-like band above the kanta, the deep recess between the mandovara and the shikara tower.