Region and Sub-regions: Cultural Facets

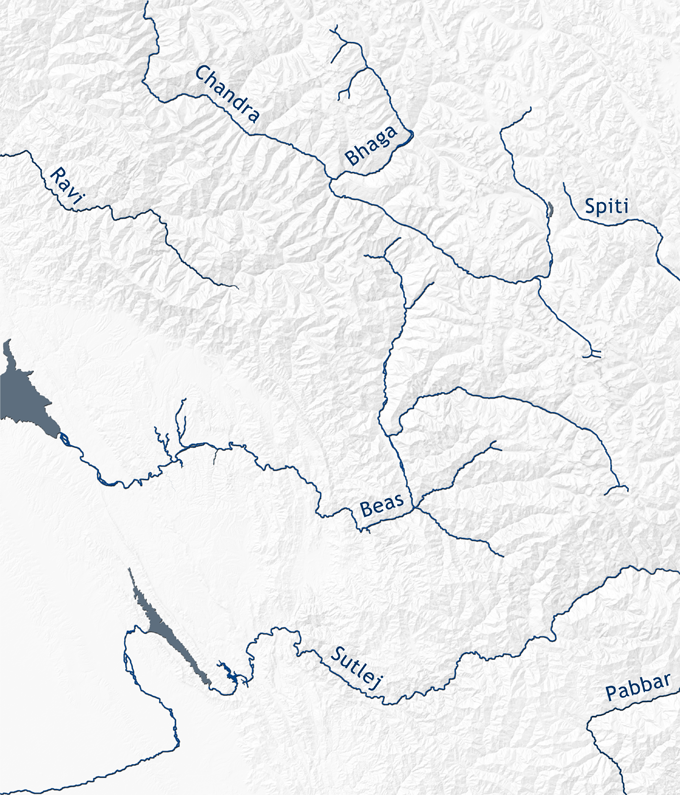

The geography of Himachal is naturally related to its topography, the mountain chains and the valleys with their rivers. The system of rivers has always played a crucial rule in the for the hill civilisations. Where the valleys were wide and fruitful the population could grow and cultural development could progress. For agriculture the Himalayan waters were essential. However, when it came to travel, the role of the rivers was manifold. Occasionally, the traffic routes were close and parallel to the rivers. But when the gorges became too narrow as it is the case with the Sutlej River, the routes became extremely dangerous and sometimes – especially in higher regions of the Western Himalayas – impassable. Then the route had to climb the slopes and follow the ridges. The situation could easily change by season when the frozen water could become routes themselves. Where the rivers became stronger, the current was too strong to use the waters for irrigation. Only the tributaries could supply the agricultural areas. Even worse, rivers became strict borders when seasonal peaks turned them into deadly streams. On the one hand the rivers created wide valleys like the Beas River of Kullu or the Ravi River of Chamba, on the other hand the narrow parts and gorges hampered communication and traffic – but also saved from invaders and aggressive neighbours. The best example for such seasonal topographic isolation is the Chandrabaga Valley of Lahul. To summarize briefly, the history of the hill state kingdoms and feudal dominions can only be understood through the topography of the country. The same is true for the transmission of cultural and artistic traditions. The best example is – up to the present – the Sutlej Valley, where the river divides the valley into a southern part belonging to Shimla District and the northern part to Kullu District. Regarding history, the major political powers within the hill states were certainly operating from their seats along the Beas (Jagatsukh and Naggar) and Mandi (Mandi Town) and Ravi (Brahmapura/Bramour, Chamba Town and Rajnagar).

The region under consideration is along the south-western face of the Western Himalayas―a region which is centred on the modern state of Himachal Pradesh. For the historical perspective, modern political borders are not always helpful when it comes to geographically locating a research subject of such kind. However, efficiency and the need to establish a proper workflow demanded an even stricter geographical focus. Therefore, for the first stage of the project the focus was on the Kullu and Lahul districts of Himachal Pradesh. The significance of the Kullu Valley is in its comparatively large number of early monuments dating back to as early as the 9th-10th centuries. The valley lies at a sea level between 1500m and 2000m. Right beyond the highest sites of pilgrimage at the end of the valley, Manali and Vashisht with its famous hot springs, the old caravan route climbs the Rotang Pass, the first major crossing over the Himalayan Range towards Lahul, Ladakh and further on to Central Asia. In comparison, the interest in Lahul results from the fact that this small sub-region is characterised by a cultural overlap by predominantly Buddhist communities in Upper Lahul and mainly Brahmanical followers in the lower parts of that valley.

The climatic situation of Kullu Valley is characterised by hot summers and cold snowy winters, and as with all other regions of the southern Himalayan face: heavy Monsoon. Its geographical position along the trading routes as well as the climatic conditions created a fortunate economic basis from trade and agriculture and, of course, pilgrimage. While major monuments were built at the eminent sites of pilgrimage and at the political centres, a significant number of smaller shrines were erected along the routes. Today, they can be found in public areas nearby sacred trees or congregational grounds, nearby temples or sometimes even inside private courtyards. Many of the smaller monuments have been re-located and placed in front of recently built temples. In many cases only surviving fragments and structural components have been preserved, and either arranged in the open in some modern temple courtyard or re-used in new temple structures.

The situation in Lahul is quite different as there is only one temple relevant for the topic of this study: The Triloknath Temple of Tonde. Nevertheless much emphasis was dedicated to another survey of this monument to gain a better understanding of its history as well as the religious-cultural dynamics and the interactive co-existence of Buddhism and Shaivaism within this intercultural zone - a geographical zone that is cut off from its neighbours for several months of the year during the winter season.

Still located within the boundaries the Kullu district, the village of Nirmand is in a side valley of the Sutlej Valley. It is the home of a number of small Nagara temples some of which are displaying important features so far unique among the surviving monuments of Himachal Pradesh. Compared to Kullu Valley, Nirmand has a quite mild climate.

On the southern side of the Sutlej, the Surya Temple of nearby Nirath is less than a 30 minutes drive on the modern road away from Nirmand. In the past however, rivers such as the Sutlej were almost impassable natural borders and even more challenging than mountain chains. This partly explains why the temple of Nirath is of a typology different to the shrines of Nirmand. And it explains why Nirath is now located in the modern Shimla District since modern district borders commonly reflect historical borders.

The region further south is again different as it is more related to the cultural centres no located in modern Uttarakhand. One of the major sites in Himachal Pradesh is Hatkoti, which has become a major attraction for pilgrimage. The mountains of that area―or rather hills when compared to the Himalayan Chain―are still around 3000m high while the valleys are at a sea level of around 1000m or lower. In the course of the project, the partly ruined monuments of neighbouring villages of Hatkoti attracted even greater interest: Saura to the South and Parahat to the North. Among those monuments the widely ruined Temple III of Parahat stands out. This temple reflects a post-Gupta artistic idiom and is certainly among the oldest monuments of all Himachal if not the oldest.

In the West of modern Himachal Pradesh is Chamba, now a modern district of the state. Its geography and history may serve as a perfect case study for a hill state, and Chamba Town which serve as its capital from the ninth century onwards, appears like a model for a traditional hill town. As already noted by J. Ph. Vogel, Chamba Town‘s topographical setting was already a natural fortress as it was located on a plateau above the conflux of two rivers, the Ravi and the Saho (or Sal). Through its history of more than 1000 years Chamba Town has never been severely devastated, neither by military aggression nor by natural disaster. The Town is the home of several religious compounds and temples. Due to the large number of monuments smaller or minor temples have not made it into any records so far just because they remained overshadowed by monuments such as the Lakshmi-Narayan or the Hari Rai temples, and therefore overlooked by scholars. If one follows the Ravi River upwards from Chamba Town towards the East one reaches Bharmor, formerly Brahmapura, the ancient regional capital from the 7th-9th centuries. Bharmor is already significantly higher than Chamba Town and thereby also much colder in winter. Temperatures fall quite below 0°C. It is rather a village than a town in the modern sense that developed around the temples of the Chaurasi Compound. Bharmor is surrounded by mountains on all sides and the Ravi Valley is rather a gorge for the most parts. One would expect this site t even safer from devastating military campaigns than Chamba Town, but that was actually not the case. In the 8th century a Tibetan force invaded the area and pillaged the compound destroying all the early stone temples, if there had been any at all. The only surviving monument from the early phase of Bharmor is wooden the Lakshana Devi Temple. The geographic location of Bharmor is of interest regarding the Triloknath Temple of Tonde which can be reached along a trail across the mountain chain to the north of Bharmor by locals by a two or three days walk. The trail is still used by herders who cross into Lahul with their goat and sheep to their summer pastures. Such traditional routes are important to understand the interaction of the cultural zones and sub-regions of Himachal.