The ongoing journey of the Skušek collection’s cultural heritage across contexts

Text by Max Frühwirt

One of the key aspects that define Ivan Skušek’s collection is the complex relationship between collector and collection and his and his wife’s, Tsuneko Kondo Kawase’s, approach to it. The pair were, in a sense, both collectors and curators, with the lived-in collection they created for themselves becoming a new stage for the many singular antiquities that make up their collection. While neither were professionally trained in museology or academia, and the great spectrum of collected antiquities makes it difficult to discern a clear collecting strategy, there are still hints that they intentionally, and with a vision for the future, amassed an impressive array of cultural heritage.

In this regard, Tsuneko almost acted as a predecessor to the modern museum curator, taking meticulous care to arrange and exhibit select pieces as part of a larger whole within the different apartments they inhabited after their return to Ljubljana. However, it is clear that the collection was not only a stage for exhibition. Rather, they actually inhabited the space with it, using the furniture for its intended purpose and possibly even arranging some of the religious objects as a sort of personal house shrine – though the latter remains up for debate – thus placing them in a new and personal context. This creation of meaning and purpose is even more remarkable given that one of the most defining features of their collection space was its combination of a wide variety of objects of different sizes, origins, and functions. It is for this reason that this week’s post aims to explore the meaning behind the singular object’s journey across time and the shifts in context it experienced throughout its ongoing history.

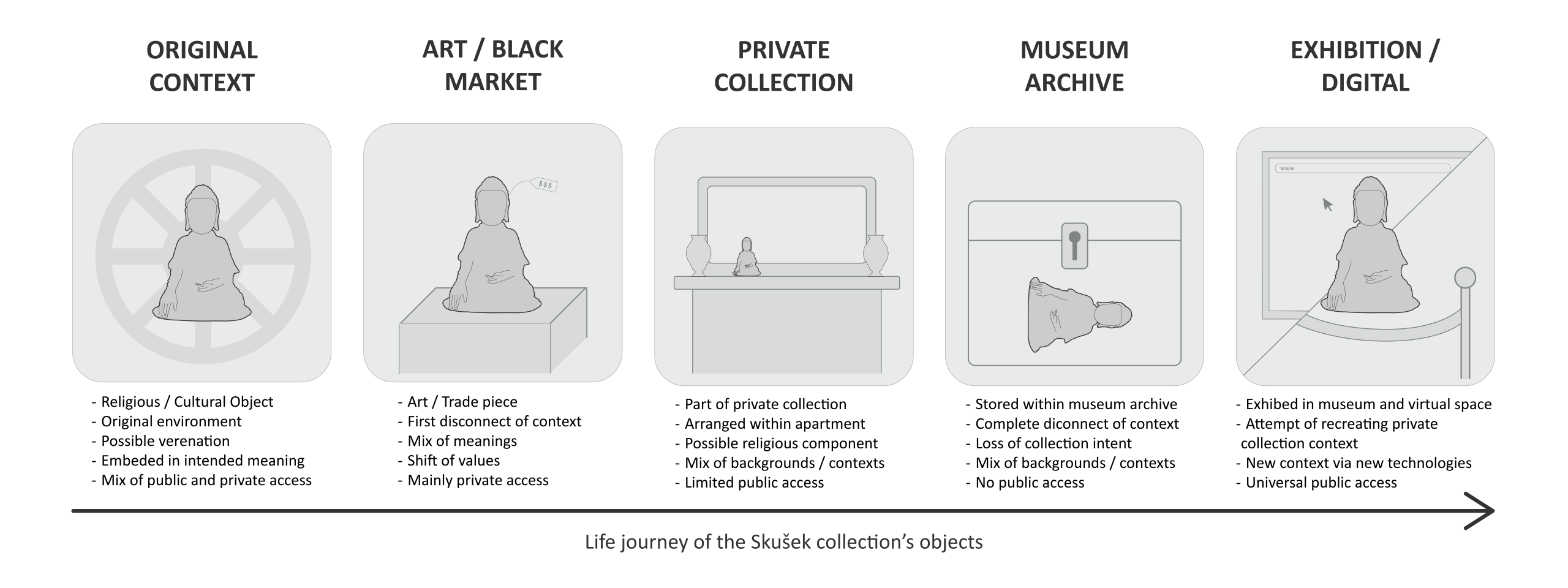

The life journey of different object of the collection across different contexts, Illustration © Max Frühwirt 2025

Over the past century, the pieces of the Skušek Collection have undergone multiple transformations – from functional objects within their original domestic settings, to commodities and curios on the art or possibly even black market, to curated pieces within the Skušeks’ lived-in museum. Even before the couples’ return to Ljubljana, the objects – especially the ones from a religious, art historical or socio-cultural background – already had inherent meaning and an intended context to be used in. However, all of this shifted, when they were combined anew within the Skušeks’ apartment, and would shift even further. After all, from there, after first Ivan and then Tsuneko passed away, they were transferred into the care of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum (SEM), as museum objects in an archive, where they have since remained and have become objects of study.

Buddha Statue on the Dresser within the Skušek apartment, Screenshot by Gerald Kozicz, Illustration by Max Frühwirt © Filmske novosti Beograd, 1957

Same Buddha statue in the archive of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum with other parts of the collection in the background, Photograph © Gerald Kozicz, 2022

Same Buddha statue (far right) on exhibition during the 2025 exhibition “Asia in the Heart of Ljubljana: The Life of the Skušek Collection” at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, Photograph © Max Frühwirt 2025

The planned digitisation and digital transformation of the Skušek Collection’s pieces into an interactive virtual reality experience marks the next step in this evolving trajectory of continuous context shifts. While the ultimate goal will be a similar recreation of the private collection experience as it was assembled by the Skušek couple on a conceptional level, an exact reconstruction of the apartments and collection environment will not be possible, due to missing or limited data and documentation of the environments as well as objects being lost to time. However, by transforming the remaining 3D representations into interactive pieces for the user to engage with on a more personal level, the created experience aims to merge some of their previous contexts together and make it palpable – marking yet another shift in their meaning and function as they enter the virtual realm.

This new context of the virtual space therefore represents both a continuation and a reinterpretation of the Skušeks’ own approach to display and engagement. In this immersive space, visitors are not only able to explore the reconstructed rooms and objects as part of an interactive narrative but will also be encouraged to form their own interpretations through free exploration and discovery. The project thereby aims to merge different elements of narrative and spatial storytelling – guiding the user through the collection’s layered history – with previously covered constructionist principles of learning, allowing for a participatory and reflective mode of engagement. Through this, the visitor is invited to become both an observer and a co-creator of meaning, echoing the Skušeks’ own curatorial practice.

Both pipes, one physical and one digital, next to each other, reconnected via the virtual during the 2025 exhibition “Asia in the Heart of Ljubljana: The Life of the Skušek Collection” at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, Photograph © Max Frühwirt 2025

This approach also prompts a fundamental question: can we ever truly recreate the original context of the Skušeks’ lived-in collection, or are we inevitably creating a new one? More than a century separates us from the couple’s home and their unique way of living with art and their collection, yet the attempt to reconstruct and reinterpret their lived-in environment reflects their fascination with the interplay between everyday life, object, and meaning. The original apartments, once the primary stage for the display of their collection, remain a central reference point for this process and will be explored in greater depth in a future post.

It is worth remembering that the Skušeks themselves, at least on some level, seemed aware of the layered meaning and importance of context their collection carried. Ivan Skušek and Tsuneko Kondo Kawase’s vision to use the purchased scaled-model of a Chinese gate house as a template for a public museum dedicated to East Asian art reveals that they saw their collection not merely as a private treasure, but as the foundation for a bigger new context of East Asian cultural heritage in Slovenia. Although their vision was never realised, it points toward a curatorial consciousness that anticipated many of the ideas now shaping its digital revival.

In this sense, the virtual environment does not aim to replicate what once was, but to continue the Skušeks’ process of recontextualisation. Each transformation – from home to museum, archive to virtual space – adds a new layer of meaning, understanding and engagement. How to make these layers visible and understandable will be one of the core challenges in its creation, but whether or not it will be possible to completely achieve that yet remains to be seen. For this reason, perhaps then, the more relevant question is not whether we can recover the original context, but how meaning itself evolves as objects move through time and space. What does context mean to a collector, to a curator, to a visitor – or even to the object itself?

References

Berdajs, Tina (2021) ‘Retracing the Footsteps: Analysis of the Skušek Collection’, Asian Studies 9, no. 3: 141–166. Open access URL https://journals.uni-lj.si/as/issue/view/739

Filmske novice 1: Zanimiva zbirka. Avtor Vladimir Perišić, © Filmske novosti Beograd,1957. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFDnA8UzBr0

Kozicz Gerald, Di Luo and Max Frühwirt (2025) ‘The Naval Officer and the Kimonoed Lady’, Orientations Vol. 56, No. 2: 94–99.

Motoh, Helena (2021) ‘Lived-in Museum: The Early 20th Century Skušek Collection’, Asian Studies 9, no. 3: 119–140. Open access URL https://journals.uni-lj.si/as/issue/view/739.